A Dog, a Fish, and Some Very Slippery Terms

Tobit and Raphael hit the road with the dog and wrestle a giant fish. Today we discuss Tobit 6.2–6.9 and define some terms: What do “apocrypha” and “deuterocanonical” mean anyway?

Episode 6 of “Bad” Books of the Bible is live! Help others find the show by leaving a rating or review wherever you get your podcasts.

Making headlines!

Screenwriter and filmmaker Paul Schrader—famous for Taxi Driver, Raging Bull, and First Reformed—recently talked with Richard Brody in the New Yorker about the current state of moviemaking. At the end of the interview, the conversation shifted to the idea of Schrader working with a streaming platform like Netflix.

“Have you ever entertained the possibility of working for a streaming service directly,” asked Brody, “whether a feature film or a series?”

“Well,” answered Schrader,

[Martin] Scorsese and I are planning something, and . . . it would be a three-year series about the origins of Christianity. . . . It’s based on the Apostles and on the Apocrypha. It’s called “The Apostles and Apocrypha.” Because people sort of know the New Testament, but nobody knows the Apocrypha. And back in the first century, there was no New Testament, there’s just these stories. And some were true, and some weren’t, and some were forgeries.

Schrader went on to say that the series would be dramatized like another of his (in)famous collaborations with Scorsese, The Last Temptation of Christ. (1)

Trade media flipped. Several outlets picked up this portion of the interview. Schrader reuniting with Scorsese on the origins of Christianity was big news. Imagine a darker, more cynical version of Mark Burnett and Roma Downey.

But what about that word: apocrypha? Schrader didn’t define it and even said that some of these stories are bogus. It would be nice to know what books he’s talking about. Alas, Brody didn’t pursue the question. As often happens with this subject, we’re left with less clarity than we’d like. So, in lieu of Schrader’s answer, we’re going to clear up some of these terms ourselves—three in particular: apocrypha, deuterocanonical, and pseudepigrapha.

Defining ‘apocrypha’

Most Orthodox Christians wince at this one. We both heard versions of “Please don’t call them that” when mentioning the concept of the podcast to friends, colleagues, and mentors. What should we say instead? Most preferred we would just say “Old Testament scripture.” That’s how we view it as Orthodox Christians.

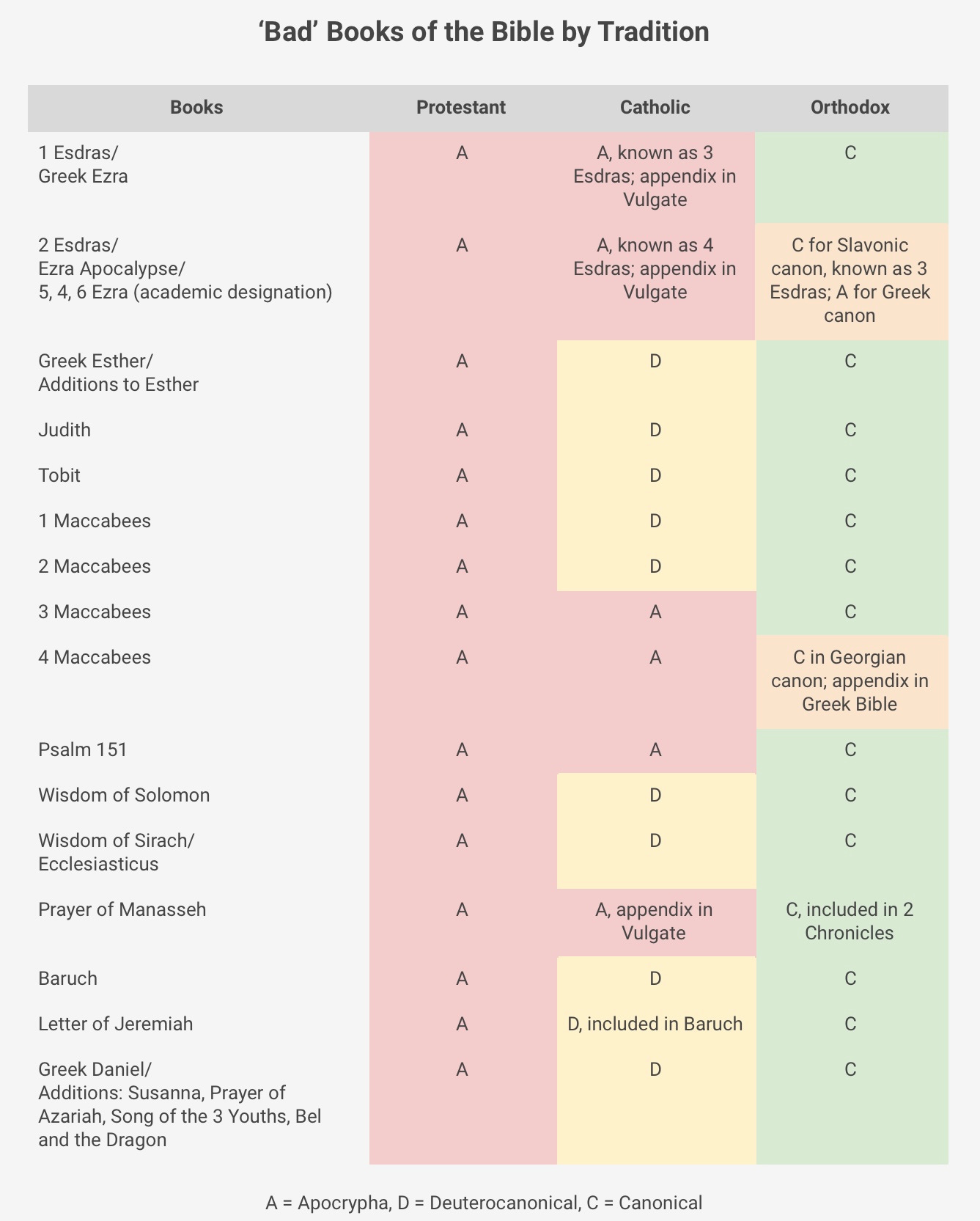

Apocrypha refers to a collection of books regarded as somehow suspect. The word itself means hidden or secret. It’s also plural—apocryphon refers to an individual book. When capitalized, the plural term Apocrypha is primarily used by Protestants to refer to the collection of several books from the Greek translation of the Old Testament that Jews later chose not to canonize: Tobit, Judith, Sirach, The Maccabean books, and so on. You can find a full(ish) list of these books in a comparative chart below.

But Christians valued, used, and preserved these books from the earliest days of the church. I (Jamey) have a set of scriptures from various world religions, edited by Jaroslav Pelikan. The volume for Christianity contains the so-called Apocrypha and the New Testament, even though these books were written before Christ—late in the Old Testament period. (2) While originally Jewish books, they are Christian scriptures now.

But not for all Christians, of course. These books received uneven treatment even in the ancient church. Some Christians regarded them as canonical, others not. There was no central authority determining what was in or out.

St. Jerome, for one prominent example, applied the term apocrypha to the books we’re talking about here. He wanted to limit the Old Testament canon to books with Hebrew originals that Jews would likewise recognize as canonical. The Catholic Encyclopedia refers to Jerome somewhat amusingly as “the great minimizer of sacred literature.” (3) He looked unfavorably on the Greek Old Testament (the Septuagint) and especially books it contained that Jews disregarded.

Despite his reservations Jerome nonetheless translated two of these books anyway: Tobit and Judith. And the Catholic church continued to use many of the books he deemed apocryphal from the Old Latin translation of the Septuagint that preceded him. As a result, use and appreciation of these books spread throughout the West as fast as missionaries, monastics, homilists, and artists could keep up.

Much later, Protestant Reformers registered their dissent from this acceptance. While some early Reformers found these books of value, later Reformers and their movement tended toward disapproval. Why? In part because Catholics used them to make doctrinal appeals Protestants didn’t approve of. Related, they further saw them as emblematic of the corruption of simple biblical religion, as best presented in the original Hebrew. They began undermining these books in print and publishing Bibles without them included—or cordoned off apart from the rest of holy writ.

In response to this and other Protestant positions, the Catholic Church convened the Council of Trent in 1546. In the fourth session of the council, they discussed the canon and the status of these books. The decree of the council not only formally approved of these books, it did so without distinguishing between them and the rest of the canonical scripture. They’re mixed right in, which reflects the state of the Bible they inherited.

Here’s the Old Testament canon as outlined by Trent, along with the ominous warning of the decree:

Of the Old Testament: the five books of Moses, to wit, Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy; Josue, Judges, Ruth, four books of Kings [1–2 Samuel, 1–2 Kings], two of Paralipomenon [1–2 Chronicles], the first book of Esdras [Ezra], and the second which is entitled Nehemias; Tobias, Judith, Esther, Job, the Davidical Psalter, consisting of a hundred and fifty psalms; the Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, the Canticle of Canticles, Wisdom [of Solomon], Ecclesiasticus [Sirach], Isaias, Jeremias, with Baruch; Ezechiel, Daniel; the twelve minor prophets, to wit, Osee, Joel, Amos, Abdias, Jonas, Micheas, Nahum, Habacuc, Sophonias, Aggaeus, Zacharias, Malachias; two books of the Machabees, the first and the second. . . . But if any one receive not, as sacred and canonical, the said books entire with all their parts, as they have been used to be read in the Catholic Church, and as they are contained in the old Latin vulgate edition; and knowingly and deliberately contemn the traditions aforesaid; let him be anathema. (4)

But a decree alone wouldn’t resolve the basic difficulty—these books had a complicated past for which some people failed to regard them as canonical. So, people reasoned, couldn’t we all just acknowledge that these books were regarded as canonical after other, less-controversial books, such as, say, Genesis or Deuteronomy? That is, couldn’t we just acknowledge a later or secondary canon?

Defining ‘deuterocanonical’

Some people, Orthodox included, refer to these books as deuterocanonical. In fact, Bishop Kallistos Ware says these books are “known in the Orthodox Church as the ‘Deutero-Canonical Books.’” (5) But this term isn’t originally an Orthodox term. It was coined in 1566 by the Roman Catholic scholar Sixtus of Siena when discussing the decree of Trent in an attempt to resolve the difficulty mentioned above.

The canonical books of the old and new testament are divided into two classes: one is prior and the other is posterior; prior, I say, and posterior not in authority, or certitude, or dignity (for each receives its value and majesty from the same Holy Spirit), but in recognition, or time: by which two things it is the case that one class precedes, the other follows.

The canonical books of the first class, which can be called Protocanonical, are of undoubted trustworthiness. . . . The canonical books of the second class (which once were labeled Ecclesiastical, and now are called by us Deuterocanonical) are those concerning which, because not immediately at the very times of the Apostles but long afterwards they came to the notice of the entire Church, there was at times among Catholics an undecided opinion. (6)

Catholics and Orthodox prefer the term deuterocanonical to apocrypha because it’s a more neutral term. It’s about time and sequence, not authority or value. As Catholic biblical scholar and priest James Vosté said about Trent: “There the Canon of the Sacred Books was defined, Deuterocanonical as well as Protocanonical; and no distinction in their authority was made.” (7)

The protocanonical and deuterocanonical books are all listed together and intermixed. There’s no sense in which the so-called apocryphal books play second fiddle in terms of authority. But the term is still somewhat complicated. For one, Trent’s list of deuterocanonical books is missing a few books Orthodox would regard as canonical (see chart below). So we can speak of “deuterocanonical books” but not “the deuterocanonical books” and mean the same thing. The lists vary.

Then there’s this additional wrinkle: Sixtus didn’t limit the term to Old Testament books. Many New Testament books were also disputed on various grounds for centuries after their composition and circulation. This situation was still fluid in the fourth century when Eusebius discussed it in his Church History:

Among the disputed writings, which are nevertheless recognized by many, are extant the so-called epistle of James and that of Jude, also the second epistle of Peter, and those that are called the second and third of John, whether they belong to the evangelist or to another person of the same name. . . .

Eusebius further mentions Revelation as a book “which some . . . reject, but which others class with the accepted books.” (8) To this day, Revelation is not found in Eastern Orthodox lectionaries because its recognition came so late in the game. (9) The Epistle to the Hebrews was likewise distrusted in the Western church.

Because of their tardy reception, Hebrews, James, 2 Peter, 2–3 John, and Revelation are all labeled “deuterocanonical” by Sixtus, along with individual passages modern biblical scholars would recognize as having sketchy attestation: Mark 16.9–20, Luke 22.43–44, and John 7.53–8.11. (10) Interestingly, Sixtus’s New Testament list is echoed in the enchiridion of his Lutheran contemporary, Martin Chemnitz—only Chemnitz actually calls these contested New Testament books and passages “apocrypha.” (11)

All this presents an amusing conundrum. If a person refers to these disputed books of the Old Testament as deuterocanonical or apocryphal, what about the end of Mark, the woman caught in adultery, or 2 Peter?

Defining ‘pseudepigrapha’

As a result of this history, when Catholics and Orthodox readers use the term apocrypha they rarely mean Tobit, Judith, and the rest. Rather, they usually mean spurious or pseudepigraphal books. And what are those? To begin with, think pseudonym—false name. Pseudepigraphal writings often are written in the name of Old Testament or New Testament luminaries, e.g., The Testament of Job, the Testament of Levi, or the Acts of Paul and Thekla.

To those we could add rewritten scripture like the Book of Jubilees, referred to in the episode as Little Genesis. Jubilees retells the story of Genesis and the Exodus account of Moses receiving the Law. Found among the Dead Sea Scrolls, the book was widely read and valued in the Second Temple period. For instance, Tobit, as mentioned in Episode 4, knows of a tradition of Noah’s wife; it’s not clear where he got it, but the author of Jubilees mentions the same fact with even greater detail.

Books such as Jubilees circulated among whoever had the means to secure them and the interest to do so. One letter found in Egypt reveals an ancient book swap. “To my dearest lady sister in the Lord,” it begins, “greetings. Lend the Ezra, since I lent you the Little Genesis. Farewell from us in God.” (12) It’s worth noting that the Ezra mentioned might be one of the many pseudepigraphal books that circulated under the scribe’s name. Depending on how you look at it, there are as many as six books of Ezra. (13)

There also were many pseudepigraphal gospels, some of which are very well known today: The Gospel of Thomas, the Gospel of Judas, the Gospel of Peter, and so on. Books such as these are sometimes called “New Testament apocrypha.”

Isidore, bishop of Seville, describes such pseudepigraphic books in his seventh-century work, Etymologies:

Many works are produced by heretics under the names of prophets, and more recently under the names of apostles, all of which have, as a result of diligent examination, been set apart from canonical authority under the name apocrypha. (14)

Bishops regularly denounced the worst of these books and directed their parishioners to not read them. As Philip Jenkins has shown, however, some of these and other pseudepigraphal works—e.g., Enochic literature—have had a formative impact on Jewish and Christian belief and practice regardless of subsequent challenges to their canonicity. (15)

For his part, Isidore seems to regard Tobit, Judith, the Maccabean books, the Wisdom of Solomon, and the Wisdom of Sirach, as canonical—though he acknowledges that Jews do not regard them all as such. Interestingly, he does seem to discount all but one Ezra book as apocryphal; as with other books contested by Jewish readers, he mentions their disputed status, but then goes a step further and doesn’t bother to actually list them at all. For Isidore, they’re not invited to the party. (16)

That’s right in line with what the Catholic church teaches even today. The Orthodox church diverges here and considers 1 Esdras, a.k.a. Greek Ezra, canonical. Pushing the boundaries somewhat, 2 Esdras is included in the Slavonic Orthodox canon. Regional churches determine canonicity in Orthodox tradition. At the furthest remove, the Ethopian church has canonized several books beyond those we’ve already mentioned—including Jubilees.

For your edification and delight, the chart below shows the three primary traditions and their attitudes about these books.

One more word!

You need a permit in fourteen U.S. states to attempt using the Greek word, anaginoskomena. It’s Athanasius’s term and more or less means “readable.” Playing off that translation, Theron Mathis refers to these books as “the readables.” (17) We could just as easily call them recommended reading.

Individual Orthodox Christians may not have an issue calling these books the Apocrypha or apocryphal for the sake of convenience or conversation with people from other traditions. But the Orthodox church, as a body, rejects the label. They are not hidden or strange or to be put away. They are for us simply scripture—part of the holy books the church uses for reading and instruction in godliness.

And that takes us, at last, to the book of Tobit and where we last left our heroes.

Journey to Rages—with a dog (6.2)

Tobias and Raphael hit the road, and they bring a companion: Tobias’s dog. It’s curious because the longer version of the story mentions the dog at this point, whereas the shorter version does not. In the shorter version the dog actually shows up in the prior chapter. Some Bibles that present the shorter version go ahead and drop the dog in here as well. And that’s a clue: the dog, wherever you find him, is important.

Why? Dogs aren’t much appreciated in the ancient world. In the Bible dogs are generally seen in a bad light. They’re famous for things like devouring Jezebel. But St. Basil the Great, commenting on Tobias’s dog, brings to mind their positive attributes: “Does not the gratitude of the dog shame all who are ungrateful to their benefactors?” Basil gives examples of dogs bringing criminals to justice and being loyal to the grave of their people. (18)

St. Ambrose has similarly good things to say: “What shall I say about dogs, who have a natural instinct to show gratitude and to serve as watchful guardians of their masters’ safety?” (19)

Like patristic scholars before them, modern scholars have found much in the little detail of the dog. Francis Macatangay, for instance, sees the dog as a picture of God’s providence. In the normal state of things, the lives of animals are well ordered. In Tobit, however, as evidence of the world gone wrong, animals cause trouble. Birds rob Tobit of his sight, the goat brings him grief, and a giant fish tries to eat Tobias (more on that in a moment). But the dog! The dog is different.

The dog is a faithful companion, content to sit in the background of the story, subtly reminding the reader of God’s persistent goodness and provision. “The striking presence of the dog allows the reader to glimpse the unseen reality that God’s positive intentionality is still operative,” says Macatangay. The dog represents “a hidden sign of hope.” (20)

Not so the fish.

The Fish (6.3–9)

On the first night Tobias and Raphael camp at the Tigris river. As Tobias washes in the river a huge fish jumps from the water going for his foot! “Catch hold of the fish and hang onto it,” yells Raphael. So Tobias holds on for dear life and yanks the fish to ground.

The narrator says the fish would have swallowed him! That’s surprising, but there are huge fish in the Tigris. Luciobarbus esocinus, or mangar, can be as big as a person. Beyond that, there’s symbolism in play here.

Consider three zones of life and activity:

The heavens, where all is well and properly ordered.

The earth, where humans strive with God to bring order to chaos.

The waters, where all is chaos and death.

The water is the realm of leviathan, behemoth, and dragons. For fish to be leaping out of the water and threatening humans like Tobias reveals a dire threat. The world is not as it should be. The fact that Tobias, with Raphael’s instruction, wrestles this fish and subdues it is a sign of restoration to come.

Readers can make even more of the fish, as the whole scene is pregnant with symbolism. St. Bede, for instance, sees a picture of Christ and the devil here in light of Pascha. Christ seized the devil, he says, and through his own death he “caught and conquered the one who wanted to catch him in death.” Bede goes on:

he seized him by the gill . . . to remove the wickedness of the ancient enemy from the heart of those whom he had wickedly allied to himself and had made, as it were, one body with him, and that, as a merciful redeemer, he might graft them into the body of his church. (21)

Raphael told him to gut the fish but keep its gall, heart, and liver. The angels says they’re useful as medicine. The Jewish Annotated Apocrypha notes that in Hebrew scripture the heart was the seat of the mind, emotion, and will; while the liver is identified in Mesopotamian literature of the day as the seat of emotions like anger and joy. And the heart of a dragon as healing is typical of fairy tales.

As is the journey of the son to heal his father, which points to something key: the Book of Tobit is working with archetypal materials. It’s one of the subtle, background reason so many people connect with this story. It resonates deeply with human hopes and experience.

At the prompting of Raphael, Tobias bags the guts and roasts some fish. The rest he salts for the adventure ahead.

Coming next week . . .

We finish the journey to Ecbatana: “The Unlucky Bride and the Matchmaking Angel.”

Richard Brody, “Paul Schraeder on making and watching movies in the age of Netflix,” New Yorker, April 22, 2021.

See Jaroslav Pelikan, Sacred Writings: Christianity: The Apocrypha and the New Testament (History Book Club, 1992).

George Reid, “Apocrypha,” Catholic Encyclopedia, Vol. 1. (Appleton Company, 1907).

https://www.papalencyclicals.net/councils/trent/fourth-session.htm

Timothy Ware, The Orthodox Church, 3rd ed. (Penguin, 2015), 194.

Edmon Gallagher, “1.1.4 The Latin Canon [prepublication version]” in Textual History of the Bible, Vol. 2, 2020.

James M. Vosté, “The Vulgate at the Council of Trent,” Catholic Biblical Quarterly 9.1 (January 1947).

Eusebius, Church History 3.25.3, 4.

Fr. Stephen De Young, “Is the Book of Revelation Canonical in the Orthodox Church?” The Whole Counsel, August 15, 2018.

Gallagher, “1.1.4 The Latin Canon.”

Martin Chemnitz, Ministry, Word, and Sacraments, trans. Luther Poellot (Concordia Publishing House, 1981), 43–45.

AnneMarie Luijendijk, Greetings in the Lord (Harvard Theological Society, 2008), 71.

A statistical and textual marvel we will have to save for a later date.

Isidore of Seville, Etymologies 6.2.50, translated by Stephen A. Barney et al. (Cambridge University Press, 2014).

Philip Jenkins, Crucible of Faith (Basic Books, 2017) and The Many Faces of Christ (Basic Books, 2015).

Isidore of Seville, Etymologies 6.2.28, 30–33.

Theron Mathis, The Rest of the Bible (Conciliar, 2011), 7. For a more scholarly treatment see Eugen J. Pentiuc, The Old Testament in Eastern Orthodox Tradition (Oxford University Press, 2014), especially chapter 3.

Basil the Great, Hexameron 9.4 NPNF 2.8.

Quoted in Sever J. Voicu, ed., Ancient Christian Commentary on Scripture, Vol. 15 (InterVarsity Press, 2010), 16.

Francis M. Macatangay, “Divine Providence and the Dog in the Book of Tobit,” Journal of Theological Interpretation 13.1 (2019). See also: Naomi S.S. Jacobs, ”’What About the Dog?’ Tobit’s Mysterious Canine Revisited” in Canonicity, Setting, Wisdom in the Deuterocanonicals, edited by Géza G. Xeravits, József Zsengellér and Xavér Szabó (De Gruyter, 2014).

Quoted in Voicu, ACCS 15.17.