Love Beyond Affirmation: A Letter to an Anglican Priest

A personal letter to a friend on the power of choice, the debates of open communion and universalism, the need for transformation, and the hope of salvation

NOTE: What follows is a more formal version of a recent email written to a friend of mine—we became traditionalist Anglicans together some two decades ago. I converted to Orthodoxy after five or six years as a devout Anglican—and at some point he was ordained a deacon, and later a priest, in the “extramural” Anglican world. At the time, most of these groups had split with the Episcopal Church over doctrine and morals. He is still a priest, but is now an avowed universalist and an “affirming priest” within the Anglican/Episcopal world.

I have revised this letter in the interests of making this post a catechetical tool; to avoid drawing my friend into any kind of online debate; and to match the tone and style of other posts on this blog. My email to him was much more casual, and less focused on explaining concepts—he doesn’t need much ‘splainin’. I share it here for illustrative purposes of positive inter-Christian conversation between friends, and to likewise offer a nuanced Orthodox interaction for the benefit of the reader.

Dear Fr. Nick:

Christ is risen! After we recently met for pints at the pub, I’ve been reflecting on our many conversations over the years—the questions we asked, the truths we pondered, the details we debated—but most of all the joy we shared in searching for the fullness of God’s truth together. Remember all those hours we spent buried in theology books? We were confirmed as Anglicans together, but we still used to joke about which of us would convert to Orthodoxy first! I will always fondly remember those conversations and time spent sorting it all out.

Looking back, I realize how formative those times were for me—how much I valued having a friend whose heart and mind were deeply engaged with the things of God, and had similar questions as I did. That’s part of why this letter is both easy and difficult to write: easy, because I still deeply admire and respect you; difficult, because it pains me to see how much our paths have diverged in recent years. You’ve shared so much about the direction your beliefs have taken, and while I value your thoughtfulness and compassion, I feel compelled to respond—not to challenge you for the sake of argument, but to explain, as honestly as I can, where I am and why.

Historic Creeds and Gospel Living

I've read about the vision for your mission parish—“Knowing each other. Loving each other. Serving others together.”—and I truly admire the commitment to embodying the Gospel in tangible ways. It always resonates with me when people of goodwill emphasize reconciliation, forgiveness, compassion, and love, and I agree with you that the historic creeds, when rightly understood, can indeed be the soil in which these virtues flourish.

You acknowledge that the creeds have been misused to divide and condemn, but you see their potential as a foundation for unity and love. I applaud this desire to reclaim these ancient statements of faith and to understand them through the lens of Christ’s love.

I, too, believe the creeds are vital, but I also believe their meaning is fixed, and that to depart from that meaning, however loving our intention, undermines their purpose.

Radical Welcome and Inclusion

Your community’s aspiration to be a place where everyone is truly welcome, wanted, and valued certainly resonates with the Orthodox understanding of God’s love. The idea that everyone is invited to enter into the mystery of Christ and to share their gifts within the community reflects the Orthodox belief that we are all created in God’s image and called to participate in the Divine life.

I also appreciate your commitment to seeking out those on the margins, speaking up for the ridiculed, and assuring outsiders of their value and inclusion—because the Orthodox Church shares these values, but exercises them in a particular way. I know your approach stems from a genuine desire to reflect Christ's love, and I recognize the sincerity behind the commitment to not insisting that everyone see everything the same way.

However, my understanding of what it means to truly welcome and include others differs in some key respects, and I want to explain why.

The Cross: A Call to Transformation

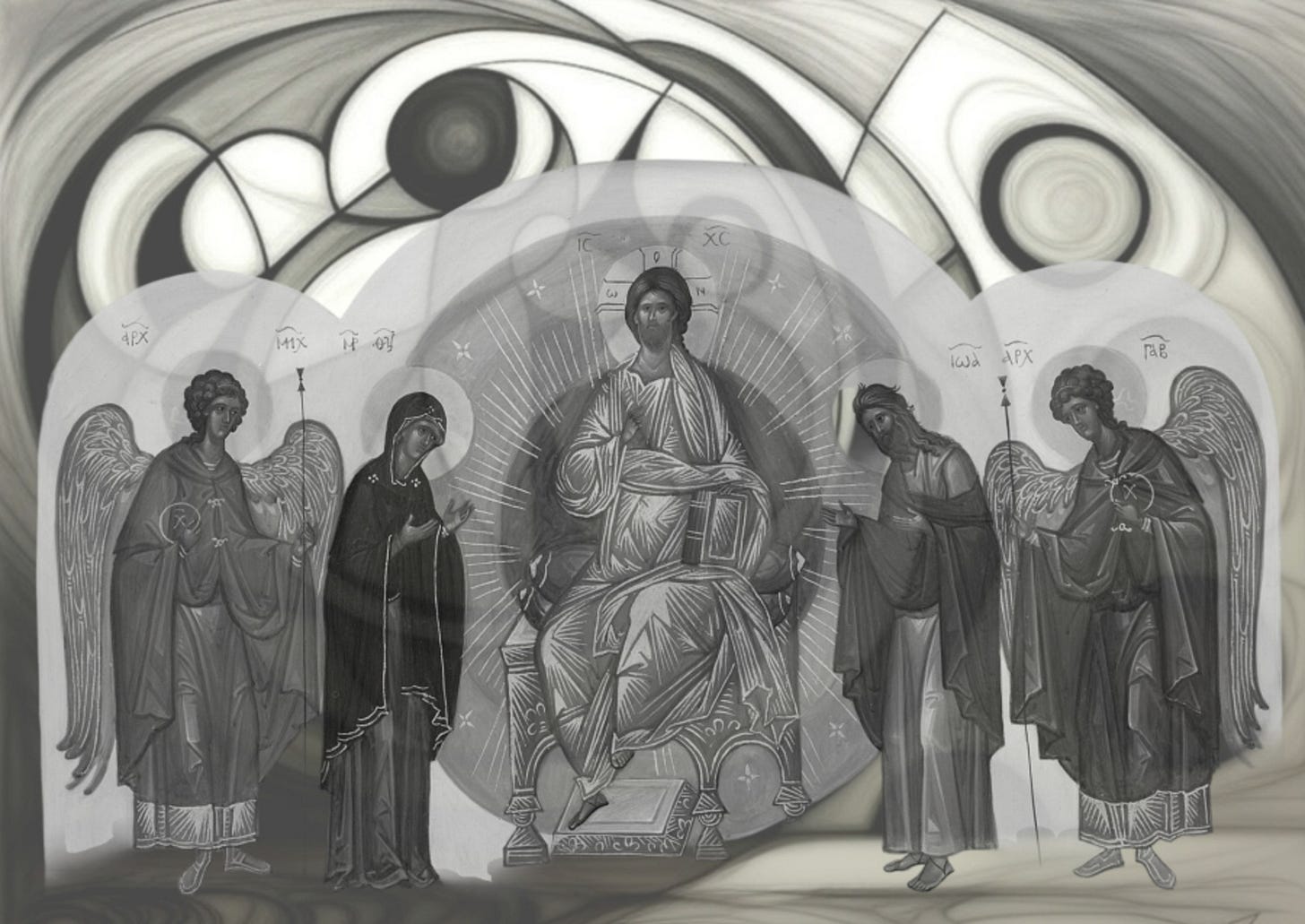

When we spoke last, you frequently mentioned the idea that the gospel requires “transformation,” and you directed me to do something like: “Look at the crucified Christ and tell Him we can’t open communion to these people.” That was a powerful image and I’ve spent a long time sitting with it. How could anyone stand before the Cross—the place where God’s infinite love and mercy are poured out for the entire world—and close their heart to another human being? The short answer is, we can’t. Christ on the Cross offers salvation to all, no exceptions.

At the same time, standing before the crucified Christ also calls us to something you mentioned many times—transformation. The Cross isn’t just a symbol of inclusion; it is the point where we die to our old selves and are reborn in His image. It’s where sin is put to death—not ignored, excused, or affirmed. For me, and for the Orthodox Church, the Cross is about more than being welcomed as we are—it’s about being changed.

This is why repentance has always been central to the Christian life. It’s not about earning God’s love or proving our worth but about turning away from the things that separate us from God so we can embrace the fullness of fellowship with Him. To kneel before the Cross is to see both the depth of my own sin and the even greater depth of Christ’s mercy. It humbles me, yes, but it also gives me hope, because it reminds me that my old self doesn’t have to be the final word. Christ’s love isn’t just acceptance; it’s the power to make us new.

Universal Salvation: Hope, Not Presumption

I’ve also thought a lot about your confident belief in universal salvation, the idea that everyone will eventually be brought into the fullness of God’s love, regardless of belief or repentance. It’s not a new idea—as you know, there are Christians throughout history who have hoped for the same, not the least of which is Saint Isaac the Syrian, whose writings I find spiritually delicious. On some level, I think we all long for this to be true. How could anyone filled with love not want the salvation of every single person? To hope for this is to reflect God’s own heart, as Scripture tells us He “desires all people to be saved and to come to the knowledge of the truth” (1 Tim. 2:4).

But Orthodoxy draws a distinction between hope and certainty. While God wills the salvation of all and provides the way through Christ, we also see in Scripture warnings about the danger of rejecting Him. Jesus Himself speaks of separation (Mt. 7:23), of narrow and broad paths (Mt. 7:13-14), and of a final judgment (Mt. 25:31-46; Rev. 20:11–15). These aren’t arbitrary threats or a balancing of love with wrath—they’re reminders of the seriousness of our intrinsic freedom.

Love, by its very nature, must be freely given and freely received. God doesn’t force salvation upon us because to do so would violate the very essence of love. When I became Orthodox, I renounced Calvinism in all its forms—including the universalist variety of monergism.

Orthodoxy doesn’t teach universalism as a certainty. We hope and pray for the reconciliation of all things, but we also recognize the mystery of human freedom. Heaven and hell, as I understand them, aren’t places in the way we often imagine. They’re the experience of God’s love—felt as joy and warmth by those who have embraced Him, but as torment by those who reject Him. Ultimately, everyone will stand in the light of God’s presence—whether that presence is heaven or hell depends on the condition of our souls.

Sin and Communion: The Path to Healing

When it comes to questions of open communion or affirming LGBTQ+ practices in the Church, I must remain faithful to two things: the desire to show unwavering compassion and the responsibility to hold to what I believe is true. Sometimes this feels like a tension, but what I’ve learned through more than 15 years of Orthodox formation is that the two aren’t mutually exclusive.

I recognize your commitment to a community where “there is only one category of human being: Loved by God,” without footnotes, caveats, or litmus tests. In many ways, this echoes the Orthodox understanding of God’s universal love for humanity. However, I believe love entails more than just acceptance, and your invitation to everyone to sit with Christ at His table in the Eucharist raises important questions for me.

Orthodoxy doesn’t reject anyone on the basis of their sins. The Church sees itself as a hospital, not a courtroom. But like any good doctor, it doesn’t just affirm where we are; it invites us into the process of healing. Christ calls all of us—LGBTQ+ individuals, straight individuals, clergy, catechists; in short, everyone—into repentance, not because He wants to shame us but because He wants to free us. Sin isn’t just breaking a rule; it’s something that damages and distorts us, something that keeps us from becoming who we’re truly meant to be.

This is why receiving communion, in the Orthodox understanding, is tied to repentance. It’s not a reward for perfection but medicine for the soul. However, like any medicine, it must be approached in the right way. St. Paul reminds us that partaking of communion unworthily brings judgment on ourselves (1 Cor. 11:27-30). For me, this isn’t about exclusion—it’s about reverence for the mystery of what the Eucharist is and what it does: it unites us with Christ and with each other in a way that calls us to transformation.

Love Is Transformation

When I think about the affirming stance you’ve taken, I don’t doubt for a moment that it comes from a deep and genuine love for others. I admire that compassion. But from where I stand in Orthodoxy, love must go beyond affirmation to transformation.

The Church is here to offer something far greater than validation—it’s here to offer newness of life.

Jesus didn’t shy away from sinners—He ate with them, touched them, healed them. But He didn’t leave them unchanged. He told the woman caught in adultery, “Go and sin no more” (Jn. 8:11). His love for her was real, but it demanded something of her because it desired her healing. That’s how Orthodox Christianity approaches sin. It doesn’t turn people away for struggling but instead calls them—and all of us—toward theosis, toward becoming more like Christ through the process of repentance and renewal.

A Shared Journey

I’ve laid a lot out here, and I hope it doesn’t come across as condescending or argumentative. That’s not my intention at all, and I would imagine you already anticipated much of what I’ve said above. If anything, this letter is a personal act of trust—a way of saying, “I respect you enough to share where I really am on these things.” I value your heart and your mind, and even though we’re in very different places now, I hope we can still engage with one another honestly, as friends who’ve learned so much from one another over the years.

At the end of the day, where I stand is grounded in the risen Christ—the One who conquered death and calls all of us to rise with Him, not just as we are but as we are made new. That’s the Christ who meets me in my own struggles and failings, who calls me to repentance not to condemn me but to heal me. I know we see some of this very differently now, but I pray God continues to guide us both deeper into His truth and love.

Thank you for taking the time to read this. I love you, my friend, and I love your dear family. I’m grateful as ever for our friendship and look forward to continuing this conversation whenever the occasion arises.

In Christ, the light of the world,

Jamey