Meet the Bad Books: A Guided Tour of the Orthodox Old Testament "Extras"

Part 2 of 2: Reintroducing the "Bad" Books of the Bible on Ancient Faith Radio (PDF Download Included)

Guided tour—exploring stories, heroes, and lessons from the “extra” Scriptures. And which “extra” books are we talking about? In this episode, Jamey walks through the major players: their history, unique themes, and surprising relevance. From Judith to Maccabees, get ready to meet some new (and old!) favorites.

The so‑called apocryphal books are the Rodney Dangerfield of the Bible. They get no respect.

If you grew up with a standard Protestant Bible, you might not even know they exist. If you had a King James with Apocrypha, you probably saw them marooned in an awkward appendix between Malachi and Matthew, separated off like that one weird cousin at Thanksgiving.

In the Orthodox Church, though, these books don’t live in the appendix. They live inside the Old Testament.

In earlier episodes of “Bad” Books of the Bible, I laid some groundwork: what the Bible is, how the canon came to be, why access to Scripture has changed so dramatically over time, and how the Old and New Testaments hang together. In this episode—and this article—I finally do what the show’s title promises: I start walking you through the “bad books” themselves.

To get there, we first need to ask two things:

What kinds of literature are we dealing with?

What do all these loaded terms—apocrypha, deuterocanon, pseudepigrapha—actually mean?

Genres in Scripture: Not Everything Is a Documentary

When we open the Bible, we’re not opening one book. We’re walking into a library. And like any library, it has sections.

I sketch eight major genres in the episode:

Law - Legal codes, commandments, and regulations, especially in the first five books of the Old Testament—the Torah or Pentateuch (Genesis through Deuteronomy).

History - Narrative accounts of events and people: Joshua, Judges, Kings, Chronicles in the Old Testament, and Acts in the New.

Biblical history doesn’t play by modern documentary rules. And even then, we like to pretend our documentaries are neutral and precise; they aren’t. A documentary arranges facts to serve a thesis.

Biblical historians do the same: they select, arrange, and emphasize with theological intention. The question isn’t “Did they have a bias?” but “What is their bias—and is it holy?”

Wisdom literature - Reflective, philosophical, practical: Job, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, and, in the Orthodox canon, books like Wisdom of Solomon and Wisdom of Sirach (Ecclesiasticus). These books help us see the world as God sees it and live accordingly.

Poetry - Expressive, often liturgical language: the Psalms, the Song of Songs. This is the Bible in hymn form, the words the people of God sing back to Him.

Narrative - Story-based texts: Genesis and Exodus are full of it, as are the Gospels and Maccabees. Narrative can overlap with history, but it’s a broader category.

It includes parables—fictional stories Christ tells to reveal truth (e.g., Matthew 13). It can also include something like historical fiction, where a tale is set in a real time and place but told with literary freedom.

The Book of Tobit probably lives here: it appears to take deliberate liberties with chronology and details to tell a theologically rich story about providence and faith.

Epistles - Letters written to communities or individuals, like Paul’s epistles and the general epistles (Hebrews through Jude) in the New Testament.

Prophecy - Messages from God delivered through prophets: Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, and the other prophets. Sometimes prophecy looks ahead; just as often it calls for repentance right now. And it is worthy of note that revelation of God is, in a sense, prophetic—truth spoken from God to His people in a particular moment.

Apocalyptic literature - A sub‑genre of prophecy marked by visions, symbols, beasts, and cosmic conflict: Revelation in the New Testament; parts of Daniel and Ezekiel in the Old. This is the genre we most often think of when we hear “prophecy,” even though it’s one corner of a larger prophetic landscape. (People often sensationalize these texts and imagine them to say more than they do.)

Knowing these genres matters because we interpret texts according to what they are. We don’t read Proverbs the way we read 1 Samuel. We don’t read Revelation like Romans. And we don’t read Tobit—or Judith, or Maccabees—well if we demand from them the kind of modern, footnoted historiography they never set out to provide.

Check out the episode below:

Defining Our Terms: Apocrypha, Deuterocanon, Pseudepigrapha, and Heresy

The word that causes the most trouble in English is “apocrypha.” It comes from a Greek word meaning hidden. Over time, it picked up a sense that something about these books is dubious, secret, or suspicious.

In popular Christian usage, “apocrypha” often does three different jobs at once:

It can refer to the books Catholics and Orthodox include in the Old Testament but Protestants do not.

It can refer to pseudepigraphal writings—texts falsely attributed to biblical figures.

It can refer to heretical books that the Church explicitly rejects.

No wonder people are confused.

As an Orthodox Christian, I don’t like using “apocrypha” to talk about the books my Church reads as Scripture. I’d rather reserve that term for books outside the Orthodox canon. Some of those apocryphal writings are spiritually helpful; others… not so much. The Protoevangelium of James, for example, is apocryphal and pseudepigraphal (falsely attributed to James), but the Church has found it useful in articulating the early life of the Theotokos. The so‑called Gospel of Thomas, on the other hand, is both pseudepigraphal and not particularly edifying.

A somewhat better term for the extra Old Testament books is “deuterocanon,” literally “second canon.” This is a term forged in the Roman Catholic world and sometimes adopted by Orthodox writers for convenience. Deuterocanonical books are those recognized as canonical in some Christian traditions but not all, and recognized somewhat later than the core books. They weren’t added at the end of church history; they were there from the beginning. (Admittedly, a few Early Fathers like Saint Jerome had heartburn over them, but they were received nonetheless.)

Then there’s pseudepigrapha itself: writings attributed to biblical figures who did not, in fact, write them. Enoch, Jubilees, and many others fall in this category. Ironically, by this technical definition even Wisdom of Solomon could be called pseudepigraphal. It’s clearly written in Solomon’s voice and style, but most scholars agree it comes from a later Jewish author, probably in Alexandria, and the Orthodox Church still reads it as Scripture. You can think of this like “In the style of [Biblical figure]…”

Finally, heretical books: texts that embody false teaching, contrary to the apostolic faith. Heresy literally means “choice”—to choose your own path over the mind of the Church. I sometimes joke, “To each his own heresy,” but there’s a serious point underneath: when someone chooses their own gospel over the one the Church received, they step outside the life‑giving stream.

So to summarize:

I avoid calling the Orthodox Old Testament extras “apocrypha.”

“Deuterocanon” is better, but still not perfect.

“Pseudepigrapha” is a technical literary category that can apply to both canonical and non‑canonical works.

“Heretical” I reserve for writings the Church has weighed, found wanting, and rejected.

What, then, do I call the books this podcast is about?

For us in the Orthodox Church, they are simply part of the Old Testament.

Download the companion slideshow to this episode!

The Septuagint: The Old Testament of the Apostles

If you want to know why the Orthodox canon looks the way it does, you have to talk about the Septuagint.

The Septuagint—often abbreviated LXX—is the ancient Greek translation of the Hebrew Scriptures produced in the third century before Christ, traditionally in Alexandria. According to the legend, seventy‑two Jewish scholars translated the Law independently and produced identical Greek versions. Whatever the details, the upshot is clear: by the time of Christ, Greek‑speaking Jews had a Greek Old Testament, and it included several books and expansions not preserved in the later standard Hebrew text.

For the early Church, this Greek Bible became the Old Testament. The New Testament itself is written in Greek, and when it quotes the Old, it usually follows the Septuagint wording. The LXX was the Bible of the apostles and the first Christians. It’s still the Old Testament of the Orthodox Church. The Orthodox Study Bible bases its Old Testament on it.

A few key points about the Septuagint:

It includes books written originally in Greek (e.g., Wisdom of Solomon, 2 Maccabees) and some originally in Hebrew where only the Greek survives.

Many Septuagint manuscripts are older than our earliest complete Hebrew manuscripts.

The Church’s liturgical life and patristic exegesis lean heavily on the LXX text.

When you hear someone say, “The Catholic Church added books to the Bible,” or, “The Orthodox tacked things on after the fact,” the historical reality is closer to the reverse. These books were there in “the Bible” that Jesus and the apostles knew. They appear in Christian Bibles really from the beginning. It’s the Protestant Reformers who removed them from the main text or shunted them into an appendix.

Myth‑Busting the Canon: Nicea, Athanasius, and Carthage

Another popular myth goes like this: “The Council of Nicea decided which books would be in the Bible.” Womp, womp. It didn’t.

The First Ecumenical Council at Nicea (AD 325 ) was convened to address Arianism and confess the full divinity of Christ. The bishops were not sitting around a table voting Matthew in and Thomas out. The canon of Scripture was a centuries‑long, grassroots process shaped by liturgical use, apostolic tradition, and pastoral discernment.

One of the key figures in that process is St. Athanasius of Alexandria. In his 39th Festal Letter (AD 367), he gives the first surviving list of the twenty‑seven New Testament books exactly as we know them today. He distinguishes these fully canonical books from other writings used for catechesis and devotion, and he uses the term “apocryphal” very narrowly—for heretical texts, not for the deuterocanonical books.

Athanasius calls the books we’re focused on here the “readable” books, ones the fathers appointed for those “who have newly joined us and who wish for instruction in the word of godliness.” In other words, they are recommended reading for catechumens. That alone ought to make modern Christians pause before dismissing them as peripheral.

Later councils, like Carthage (AD 397), reflect and confirm a broad consensus already present in the churches. They do not create the canon out of thin air; they recognize what the Spirit has already stamped on the heart and worship of the Church.

The Orthodox Old Testament Canon: Same Story, Longer Shelf

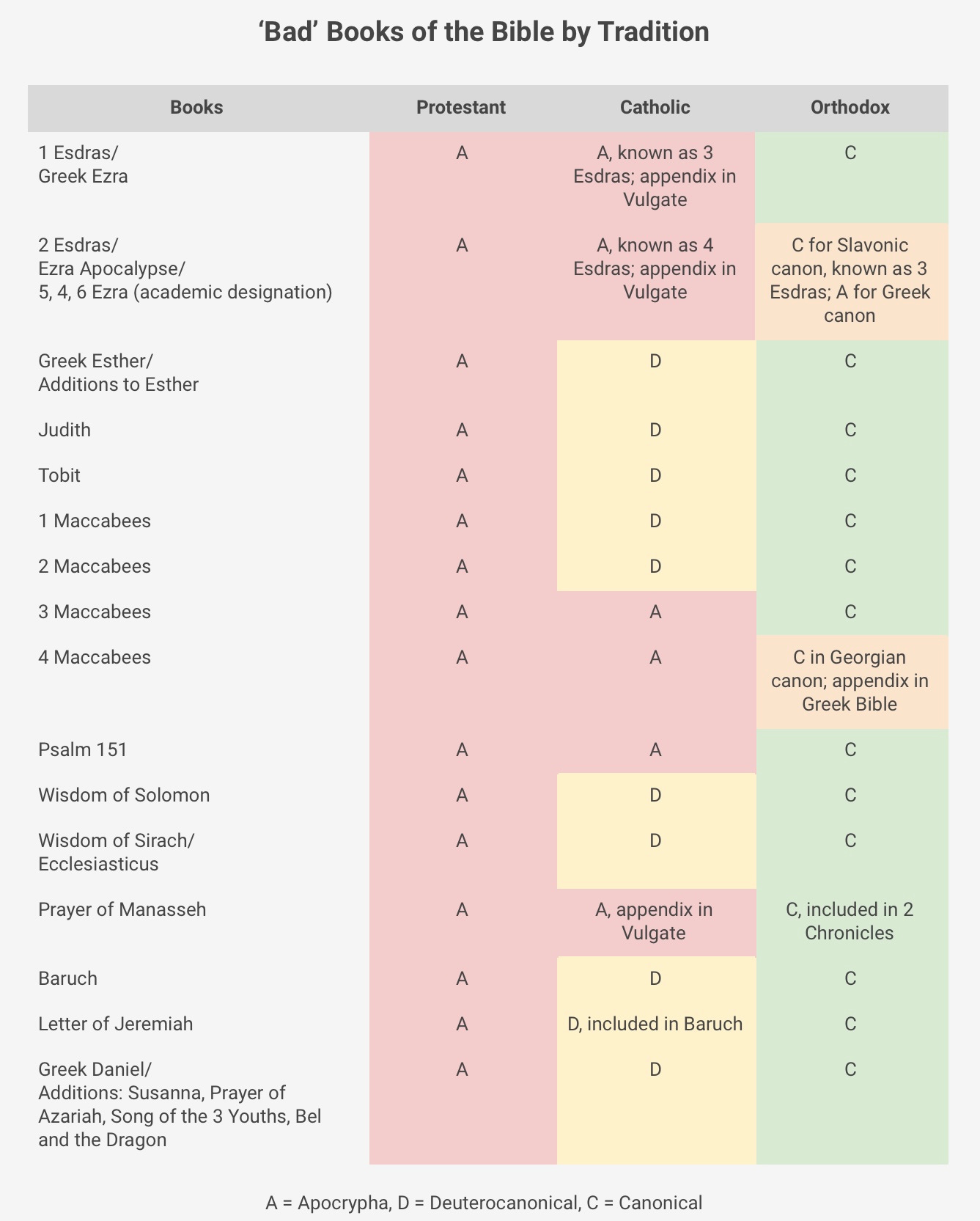

So what actually distinguishes the Orthodox Old Testament from the standard Protestant one?

From Genesis through Chronicles, all three major traditions—Protestant, Catholic, Orthodox—are reading essentially the same story, though we use slightly different book names:

1–2 Samuel are 1–2 Kingdoms for us.

1–2 Kings become 3–4 Kingdoms.

1–2 Chronicles are sometimes labeled 1–2 Paralipomenon.

After that shared core, the Orthodox canon keeps going. In addition to the books Protestants know, we include:

1 Esdras (our “1 Ezra”; the Protestant “Ezra” is our 2 Ezra, confused yet?),

Tobit,

Judith,

1–3 Maccabees (with 4 Maccabees as an appendix in many Orthodox editions),

Wisdom of Solomon,

Wisdom of Sirach (Ecclesiasticus),

Baruch and the Epistle of Jeremiah,

Psalm 151,

additions to Esther,

extra material in Daniel: Susanna, Bel and the Dragon, the Prayer of Azariah, and the Song of the Three Youths,

and the Prayer of Manasseh (often printed with the Psalms or in the service books).

Local Orthodox traditions—Georgian, Slavonic, and especially the Oriental Orthodox (and Ethiopians!)—have their own nuances, but that’s the core of the Orthodox picture.

A Whirlwind Tour of the “Bad Books”

Let me introduce a few of these briefly, with special attention to Tobit, Sirach, and the Maccabees.

Tobit: Providence in Exile

Tobit 4:19 says, “Bless the Lord your God always, and desire of him that your ways may be directed, and that all your paths and counsels may prosper.”

On the surface, Tobit is the story of a righteous Israelite living in Assyrian exile, his blindness and bitterness, and the journey of his son Tobias to recover a debt. But along the way we meet an archangel in disguise (Raphael), a demon who has killed seven bridegrooms in a row, a long‑suffering young woman named Sarah, a faithful dog, and a fish that nearly eats our hero’s foot.

Historically, the book was probably written between about 225 and 175 BC, but it is set after the fall of the northern kingdom (around 720 BC). That deliberate bending of timelines is one reason many scholars see Tobit as a kind of didactic historical fiction. It’s not lying to you; it’s telling the truth in story form, using real places and periods to frame its message.

And that message is profoundly Orthodox: God’s providence runs underneath everything. Even in exile, even in suffering, even in the small choices of travel plans and marriages, the Lord is at work. Tobit and Tobias insist on almsgiving, prayer, and obedience to the Law when it would be easier to disappear into Assyrian life. Sarah cries out to God in despair instead of surrendering to the demon’s script. Raphael quietly orchestrates meetings, healings, and exorcisms behind the scenes.

Tobit feels, in other words, like a story written for anyone who has ever wondered, “Is God still paying attention?” The answer it gives, through angels and dogs and a very large fish, is yes.

Judith: Holy Cunning

Judith 16:16 declares, “For the mountains shall be moved from their foundations with the waters. The rocks shall melt like wax at your presence, yet you are merciful to those who fear you.”

Likely composed in the late second century BC, Judith reads like an ancient thriller. A beautiful, devout widow outwits an invading general, gets him drunk, and cuts off his head to save her city.

The historical details are intentionally scrambled; the point is not to give a precise chronicle but a hero‑tale of courageous faith and holy cunning.

Wisdom of Solomon: The Two Ways and the World to Come

“Wisdom is radiant and unfading, and she is easily discerned by those who love her and is found by those who seek her” (Wisdom 6:12).

Probably written in the first century BC by an Alexandrian Jew, Wisdom of Solomon stands squarely in the wisdom tradition of Proverbs but pushes further into themes like the two ways (life and death, righteousness and wickedness) and the hope of life after death. It reflects on what it means for the righteous to suffer and the wicked to prosper, and it insists that God’s justice extends beyond the grave.

Wisdom of Sirach (Ecclesiasticus): A Second Proverbs for the Church

“Stand up for what is right, even if it costs you your life. The Lord God will be fighting on your side” (Sirach 4:28).

Written around 180–175 BC by Jesus ben Sirach, a Jewish sage in Jerusalem, and later translated into Greek by his grandson, Sirach is essentially a second Proverbs on steroids. It ranges over friendship and speech, money and marriage, priests and kings, honoring parents, avoiding gossip, guarding your tongue, and the fear of the Lord as the beginning of wisdom.

Unlike most Old Testament authors, Ben Sirach actually names himself and locates his work clearly in the Second Temple world. That alone gives us a rare window into Jewish piety between the prophets and Christ. The book was beloved in Judaism and in the early Church. Western Christians even nicknamed it “Ecclesiasticus,” the “church book,” because it was used so heavily in catechesis.

The New Testament doesn’t quote Sirach directly with a “thus says the Scripture,” but its fingerprints are everywhere—in James’s concern for the tongue, in the Sermon on the Mount’s praise of mercy, in the Epistles’ concern for humility and almsgiving.

Sirach reveals the religious and spiritual tone of the Jewish world of Jesus.

Baruch and the Epistle of Jeremiah: Exile, Idols, and Hope

“Learn where there is wisdom, where there is strength, where there is understanding, so that you may at the same time discern where there is length of days and life, where there is light for the eyes and peace” (Baruch 3:14).

Attributed to Baruch, Jeremiah’s scribe, but likely written much later, Baruch offers theological reflection on sin, exile, and God’s mercy. The attached Epistle of Jeremiah (often counted as Baruch 6) is a blistering critique of idols and idolatry.

Together they speak to Jews scattered from their homeland and to anyone tempted to trust in the glittering gods of empire instead of the living God. Certainly something we could all stand to be reminded of in the modern era.

The Greek Daniel: Susanna, Bel and the Dragon, and the Songs

In the Septuagint, Daniel includes several narratives not found in the later standard Hebrew text.

Susanna tells of a righteous woman falsely accused by corrupt elders and vindicated through Daniel’s Spirit‑filled cross‑examination. It is an early meditation on justice, chastity, and God’s defense of the innocent.

Bel and the Dragon showcases Daniel dismantling idol worship and unmasking fraud in a way that feels almost like an ancient crime story. We love a good detective tale around here.

The Prayer of Azariah and the Song of the Three Youths expand the fiery furnace narrative, giving us the repentant and doxological words of the three young men as they refuse to bow to the image and are preserved in the flames with a fourth figure “like a son of God” (Daniel 3 in LXX). The Church has always seen this as a theophany, a revealing of Christ our God in the Old Testament.

Additions to Esther

The Greek additions to Esther supply exactly what many readers of the Hebrew book feel is missing: explicit prayer, fasting, and references to God’s providence. They turn a story that—on the surface—never names God into one that constantly acknowledges His hidden hand.

Psalm 151

This short psalm, speaking in David’s voice about his anointing and victory over Goliath, long existed only in Greek, Latin, and Syriac. The discovery of a Hebrew form among the Dead Sea Scrolls confirmed it as an ancient piece. Orthodox Christians have always prayed it as a kind of doxological coda to the David story; most other traditions simply omit it.

1 Esdras

1 Esdras overlaps with parts of 2 Chronicles, Ezra, and Nehemiah and includes the famous story of the three bodyguards debating what is strongest—wine, the king, women, or truth—with truth winning the day. Likely written between 150 and 100 BC, it was a key source for Josephus. In the Orthodox canon it leads naturally into 2 Esdras (the Protestant Ezra), filling out the picture of temple restoration and return from exile. (The story of that text sounds like a rollercoaster!)

The Maccabees: History, Martyrdom, and Reason over Passion

The four books of Maccabees give us different angles on Jewish suffering, resistance, and faith under pagan rule.

1 Maccabees is a fairly straightforward historical account of the Maccabean revolt against Antiochus IV Epiphanes in the second century BC. It could easily be a Ridley Scott film with all the intrigue and battles. If you want to know what happened in broad strokes, start here.

2 Maccabees covers some of the same ground but with a different emphasis. It zooms in on the martyrdoms of faithful Jews who refuse to apostatize, on prayers for the dead, on the hope of resurrection, on the intercession of the righteous. Where 1 Maccabees gives you the skeleton of events, 2 Maccabees gives you the beating heart—the theological meaning of those events. Together they form a bridge from the Old Testament into the world of the New, where resurrection hope and martyrdom will shape Christian witness.

3 Maccabees isn’t about the Maccabean revolt at all. It tells of persecution and deliverance of Jews in Egypt under Ptolemy IV, probably to explain and sanctify a local festival. Think of it as an ancient thanksgiving story for a particular community that still speaks to the wider world about God’s care for His people even in a pagan land.

4 Maccabees, usually appended in Greek Bibles rather than fully canonical, is a philosophical sermon on the theme that “pious reason is master of the passions.” It uses the stories of the Maccabean martyrs as case studies in how a mind formed by the Law can govern fear, pain, and desire.

If you’ve ever wondered what Stoic philosophy sounds like when baptized into Judaism, 4 Maccabees is your book—and it has had a real influence on Orthodox reflection on asceticism and martyrdom.

Taken together, the Maccabean literature explains not only a crucial chapter of Jewish history but also the spiritual atmosphere into which Christ was born: a world where fidelity to God might cost you everything—and where God’s people believed, stubbornly, that He could raise the dead.

The Prayer of Manasseh

Finally, the Prayer of Manasseh gives us the contrite voice of one of Judah’s worst kings (see 2 Chronicles 33). It’s a short Greek prayer that the Orthodox Church places prominently in the service of Great Compline during Great Lent.

Alongside Psalms 50/51 and 101/102, it teaches us how to say, “I have sinned more than the sands of the sea,” and yet still throw ourselves on the mercy of God. It’s hard to imagine a more practical, usable text for the life of repentance. (We did an episode on it a while back, and think it is worth your time.)

Why These Books Matter

These are not curiosities for footnotes. They shaped the piety of Second Temple Judaism (c. 516 BC - AD 70). They fed the imagination of the apostles. They were read aloud in early churches and recommended by saints like Athanasius for catechumens. They continue to form the prayer life, preaching, and theology of the Orthodox Church.

If you want to follow along with this material in print, a good English companion is the Orthodox Study Bible, whose Old Testament is based on the Septuagint. For exploring other ancient Jewish and Christian texts that sit outside the canon, Fr. Stephen De Young’s book Apocrypha is a very helpful guide.

In “Bad” Books of the Bible, the aim is not merely to defend these books’ place in the canon but to walk with you through them: to show how Tobit teaches us providence, how Judith models courage, how Wisdom and Sirach train us in virtue, how Baruch and the Maccabees speak to exile and resistance, how Daniel’s Greek additions deepen our understanding of God’s presence in the furnace, and how the Prayer of Manasseh teaches every one of us how to say, “I have sinned,” and mean it.

These “bad books” might just end up being some of the best gifts you didn’t know your Bible had.