Orthodox Communion: A Boundary of Faith, Not a Barrier to Love

A catechist's explanation on why communion is reserved for Orthodox Christians who have prepared themselves

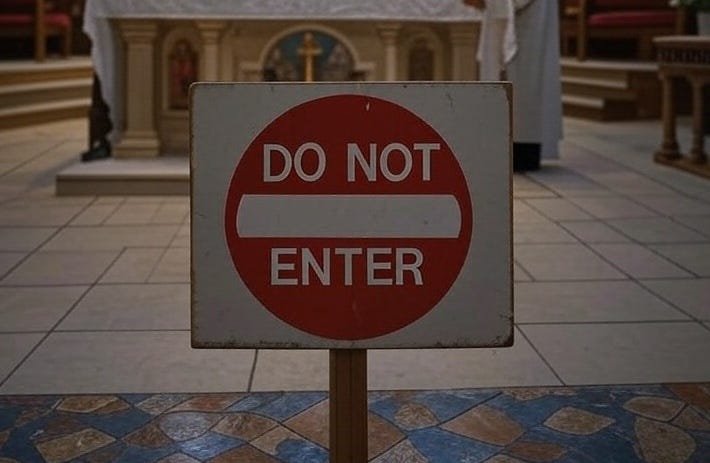

Hello Jamey, thanks for reaching out. Things have been well on our end—we are still have many questions regarding Orthodoxy. Even more when we were denied communion for not being Orthodox Christians—and have not been back since.

Dear Friends,

I’m so glad to hear from you and to know that things are well on your end. As a catechist at Saint Mark, it is my joy and responsibility to walk alongside those who are inquiring about the Orthodox Christian faith at our parish, and I greatly appreciate you sharing your concerns.

I understand that being denied communion during your visit to our church must have been surprising, perhaps a disheartening or confusing experience, especially given your background in a non-denominational, evangelical setting where open communion is frequently the norm these days. I want to assure you that this practice is not meant to be a personal rejection but is rooted in the ancient theology and discipline of the historic, Christian faith.

Allow me to explain the Orthodox approach to communion (synonymously called the Eucharist), and why it is reserved for Orthodox Christians in good standing. I hope this will provide clarity, foster understanding, and perhaps encourage you to continue your journey of faith along with us.

Union and Communion?

To begin, let me affirm that the best Orthodox thinkers value hospitality and desire unity among all who seek to serve Christ. We long for the day when all who profess Christ can share in the same chalice as a sign of our oneness in Him.

However, our practice of closed communion—where the Eucharist is offered only to baptized and chrismated Orthodox Christians who are prepared through confession and fasting—stems from our theological understanding of what the Eucharist is and what it signifies.

In Orthodoxy, the Eucharist is not merely a symbolic act or a communal meal of remembrance/thinking really hard about Jesus and the cross—though it does include elements of memory and fellowship. Rather, we believe it is the very Body and Blood of Christ, a mystery (or sacrament) through which we are spiritually united to Christ Himself and to one another in the deepest possible way.

This belief is not unique to Orthodoxy—many Christian traditions affirm the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist—but the implications of this belief shape our practice in a distinct way. Because we see the Eucharist as the pinnacle of our union with Christ and His Church, we approach it with reverence and caution.

The Apostle Paul warns in 1 Corinthians 11:27-29 that partaking of the Lord’s Supper “unworthily” can bring judgment upon oneself—this is a very serious warning!—and the Orthodox tradition stresses, as a consequence, that one must be properly prepared and in full communion with the Church to receive. It is not about judging the sincerity of someone’s faith—but about safeguarding the integrity of the sacrament and the spiritual well-being of the individual.

Key Takeaways:

The Orthodox Church practices closed communion, reserving the Eucharist for baptized and chrismated members, due to our belief in its sacramental nature as the Body and Blood of Christ.

From ancient times, communion among Christians was seen as a sign of full unity in faith and Church life—quite a different from the open communion common in many Protestant traditions since the mid-to-late 20th century.

Being denied communion is not a personal rejection but an invitation to explore Orthodoxy further, with the hope of eventual full participation through catechesis and sacramental initiation.

Return to the parish, ask questions, and engage with our community as you continue your spiritual journey.

Open Communion: A Novelty?

Historically, closed communion was the standard practice across all major Christian traditions—Orthodox, Catholic, and even Protestant groups—until relatively recently. In the Orthodox Church, this practice has remained unchanged since the earliest centuries of Christianity. Our approach is not a modern innovation but a continuation of the Apostolic tradition, where communion was a sign of full unity in faith, doctrine, and ecclesiastical life.

To receive communion in an Orthodox church, one must not only believe in Christ but also be a member of the Orthodox Church, which entails accepting its teachings, being baptized and chrismated (confirmed) in the Orthodox manner, and living under the spiritual guidance of an Orthodox priest or bishop.

I recognize that this stands in stark contrast to the open communion practices you may be accustomed to in evangelical or non-denominational settings, where the Lord’s Supper is often extended to all who profess faith in Christ, regardless of denominational affiliation. This shift toward open communion in many Protestant churches, particularly in the 20th century, was influenced by the ecumenical movement, which sought to emphasize shared Christian identity over doctrinal differences. While this gesture of inclusivity is commendable in its intent to foster unity, the Orthodox perspective holds that true unity cannot be achieved by overlooking differences in belief and practice.

Instead, we believe that communion must reflect an already existing unity in faith and life, rather than serve as a means to create it. As Fr. Charles Bell, Ph.D has put it:

In the historic understanding of the Church, Communion has always been understood as the goal, the climax and expression of our unity in Christ. Today there are over 25,000 denominations worldwide and among them are many different views of Jesus.

The Orthodox practice closed communion, not for triumphalistic reasons, but for very important theological reasons. In doing so they follow the practice of the ancient Church; a practice that was retained by the Reformers.

Communion is a Corporate Act by Definition!

This brings me to the heart of why you were not able to receive communion during your visit. In Orthodoxy, communion is not just a personal act between the individual and Christ; it is a corporate act that signifies membership in the Body of Christ, which we understand in its fullness to be the Orthodox Church.

When someone who is not Orthodox approaches the chalice, even with a sincere heart, they are not in full communion with the Church’s faith and life. Offering communion in such a case would, in our view, be a false sign of a unity that does not yet exist. It would also potentially place both the individual and the priest in a position of spiritual risk, as it could imply a casualness toward the sacrament that does not align with our understanding of its gravity.

I want to emphasize that this practice is not about exclusion or superiority. It is not a statement that we doubt your faith in Christ or your commitment to Him. But the Eucharist reflects our shared beliefs, sacramental initiation, and spiritual life within Orthodoxy.

I regret any sense of rejection you may feel, and wish we had a chance to better prepare you. My hope is that you can see it as an invitation to continue exploring Orthodoxy, to understand why we hold to these ancient practices, and perhaps even to consider joining us fully on this path.

Let’s Talk

If you are willing, I would love to meet with you over coffee to discuss your questions and experiences further.

The journey of becoming Orthodox is a gradual one that involves catechesis—a period of learning about the faith, its history, theology, and practices—followed by the sacraments of christmation and/or baptism for those who have not been initiated in the Orthodox Church. During this time, you would be warmly welcomed to attend services, participate in the life of the community, and grow in understanding of our traditions. Even now, though you cannot receive communion, you are invited to fellowship with us, to pray with us, and to receive the blessed bread (antidoron) distributed at the end of the Liturgy.

Coming from a non-denominational, evangelical background, you may be used to a more individualistic approach to faith, where personal belief in Christ is the primary criterion for participation in communion. Orthodoxy, by contrast, is communal and sacramental. We see the Church not as a loose association of believers but as the living Body of Christ, with visible boundaries and a shared way of life.

This can be a significant shift in perspective, and I encourage you to ask any questions you have about it. How does this view of the Church compare to your own experience? What aspects of Orthodoxy intrigue or challenge you? I’m here to listen and to help.

In the meantime, I hope you will consider paying us another visit. While communion is reserved for Orthodox Christians, your presence with us is a blessing, and there are many ways to engage with the community. Attend the Divine Liturgy, join us for fellowship afterward, and let us know how we can support you in your spiritual journey. If there are specific teachings or practices—whether about communion or anything else—that you’d like to explore, I’m happy to provide resources or arrange conversations with one of our priests or other knowledgeable members of the community.

Conclusion

Finally, I want to reiterate that the Orthodox practice of closed communion is not a barrier meant to keep you out but a boundary that reflects our deepest beliefs about the nature of the Eucharist and the Church. It is my heartfelt prayer that this explanation helps to heal any sense of hurt you may have felt and opens the door to further dialogue.

The Orthodox Church has a rich and ancient tradition, one that has sustained believers through centuries of challenge and change, and I believe it has much to offer to those who seek a deeper connection with Christ. On my own journey I struggled with this and other related issues, but when I realized the Orthodox Church held the pearl of great price, I sold everything to obtain it (Matthew 13:45-46).

Please know that you are always welcome to reach out, to visit, and to learn more.

With love in Christ,

Jamey

Interested in learning more? Here are a few links from around the interwebs that might further illumine your understanding:

“Why Not ‘Open Communion’?” by Father John Breck

“On Closed Communion” (from the Praying in the Rain podcast) by Father Michael Gillis

“ONE LORD, ONE FAITH: Why Orthodox don’t practice Open Communion” by Abba Seraphim

“Closed communion” (Wikipedia page)