Pascha Every Sunday: A Field Guide to the Calendar of the Orthodox Church

Centered on the Feast of Feasts and its weekly echo on Sunday, the liturgical year isn't merely rules to follow—it's an invitation to nest your busy, modern life inside the bigger story of salvation

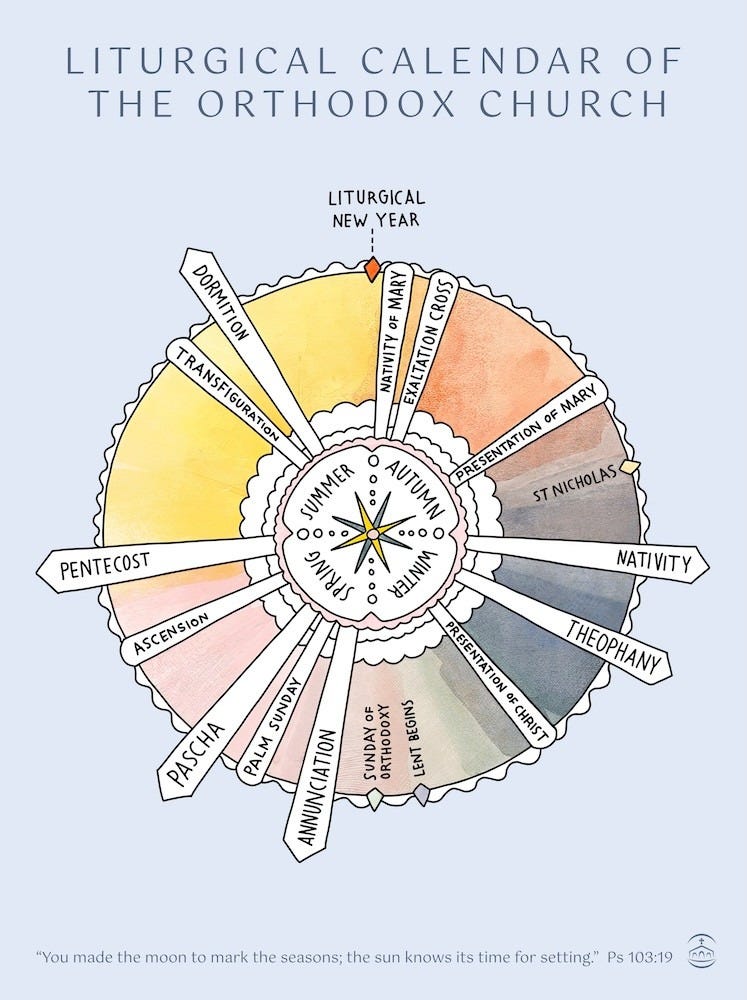

Those new to Orthodox Christianity sometimes find themselves with basically two calendars on the fridge now. One is familiar: school schedule, work deadlines, national holidays, tax day (Kyrie eleison!), birthdays, and of course a veterinary appointment for Fido.

The other—maybe a glossy one from a monastery or a simple one from a parish bookstore—is crowded with saints’ names, little fish icons, color‑coded fast days, and feasts with names like “Entry of the Theotokos” or “Meeting of the Lord.”

It looks beautiful but slightly overwhelming—like your iPhone calendar married a medieval manuscript. Most new Orthodox Christians (and a lot of old ones) feel this tension: I already live in one kind of time. How do I live in this other one too?

Fr. Steven Kostoff, who sees every moment as a gift and not something to be flittered away, puts it like this:

In the fallen world that we occupy, time has become inextricably linked to mortality and death, but it still remains a gift, as do all aspects of God’s creative will, now redeemed by the advent of Christ. Often, we hear—and may even use—the dreadful phrase “to kill time,” either out of boredom or in waiting for something “important” to happen. Yet our Christian vocation is to “sanctify time” as our movement toward the Kingdom which has no end. Every moment counts, because every moment is a gift from God.

The good news is that the Church’s year is not meant to be a second full‑time job. It’s a way of telling time with Christ, slowly letting His life, and the lives of His saints, become the framework for our own.

Why the Church Has Its Own Calendar

Ever wonder why the Church has its own calendar? It’s really about storytelling. It’s how we walk through the life of Christ—and the life of His Mother, His Apostles, and His saints—over and over until those stories sink deep into our hearts.

Now, the regular calendar we all use isn’t bad, but it focuses on different things—national holidays, wars, important figures in history, and dates that matter in daily life. The Church calendar, on the other hand, revolves around the big moments in our faith: the Incarnation, Cross, Resurrection, Ascension, Pentecost, Dormition—and, of course, all the incredible examples over the centuries people saying “yes” to Christ despite the intense personal cost.

So, next time you glance at a church calendar, don’t just think of it as another list of dates. See it as the Church’s way of showing us who we are and reminding us that we’re living in God’s time, that time itself can by sanctified and made holy, set apart.

The Twin Gravitational Centers: Pascha and Sunday

Okay, before we dive into the nitty-gritty, it's helpful to understand the two major focal points that shape the Orthodox Church's calendar: Pascha and Sunday. Think of them as the big gravitational centers of the Orthodox liturgical universe.

Pascha: Feast of Feasts

Pascha (that’s Easter) isn't just another holiday on the list. It's the most important one—the “Feast of Feasts” as it is sometimes called. It’s our annual celebration of Christ's Resurrection, and it's a huge deal, with Holy Week leading up to it, and then Bright Week following it. Great Lent is the long period of preparation beforehand, and the Sundays after Pascha (Thomas Sunday, the Myrrhbearers, the Paralytic, etc.) all riff on its themes.

If you imagine the Church’s year as a wheel, Pascha is the hub. Everything else—fasts, feasts, commemorations—turns around it.

Sunday: Weekly Pascha

We believe it is Easter every Sunday. So when we speak of Sunday, which the New Testament already calls “the first day of the week” (Acts 20:7) and “the Lord’s Day” (Revelation 1:10), remember that for the Church, every Sunday is a little Pascha. That’s why the Resurrection theme shows up in the hymns week after week, not just once a year.

(And it is worth noting that even Sunday’s Liturgy is interconnected with other services—Vespers, Matins, and so on. Together, they work to incrementally instruct us and lead us in worship of Christ our true God.)

For most of us, the simplest way to start “living the Church’s year” is to let Sunday Divine Liturgy really become the center of our week. If Pascha and Sunday are in place, the rest of the year has something solid to hang on.

The Twelve Great Feasts on One Page

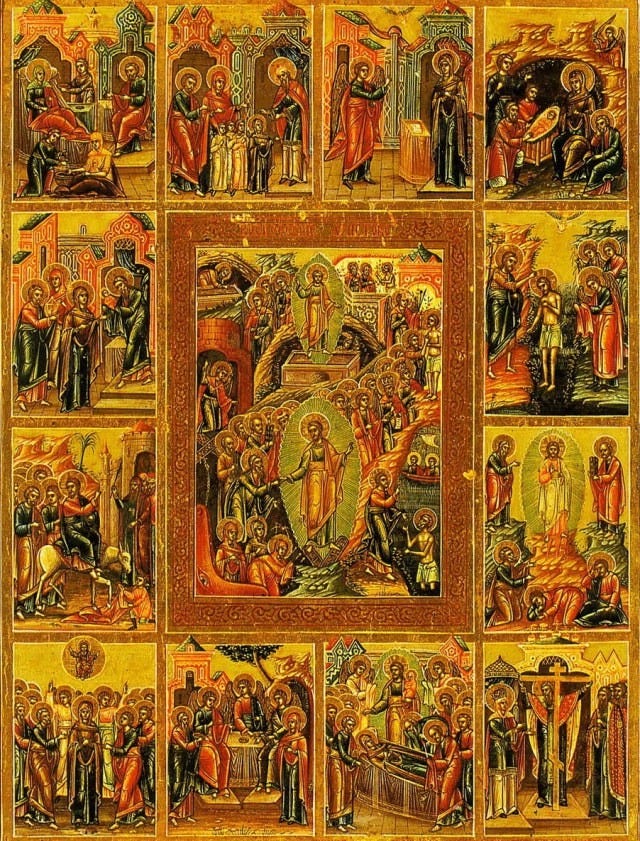

Beyond Pascha, if the Orthodox year is telling us a story, then the Twelve Great Feasts function like major chapter headings in that story. In very brief strokes:

Nativity of the Theotokos (September 8) - The birth of Mary, the future Mother of God—God’s preparation for the Incarnation begins.

Elevation of the Holy Cross (September 14) - The discovery and veneration of the Cross; the paradox that a device of execution becomes the sign of victory.

Entrance of the Theotokos into the Temple (November 21) - The young Mary being brought into the Temple—her life being offered to God.

Nativity of Christ (December 25) - Christmas: the Word becomes flesh; God with us in our own human life.

Theophany (January 6) - Christ’s baptism in the Jordan; the Trinity revealed; the waters of the world blessed.

Meeting of the Lord (February 2) - The forty‑day‑old Christ brought to the Temple; Simeon and Anna recognize him as the Light of the nations.

Annunciation (March 25) - Gabriel’s announcement to Mary; her “Let it be” that opens the door to the Incarnation.

Entry into Jerusalem / Palm Sunday (Sunday before Pascha) - Christ enters the city as King, riding toward His voluntary Passion.

Ascension (40 days after Pascha) - Christ returns to the Father in His glorified humanity; humanity is seated at the right hand of God.

Pentecost (50 days after Pascha) - The Holy Spirit descends; the Church is publicly born; the nations of the earth are called to fellowship with God in the Church.

Transfiguration (August 6) - Christ shines with uncreated light on Mount Tabor; His divinity is revealed through His humanity.

Dormition of the Theotokos (August 15) - The falling asleep of Mary and her being taken into the presence of her Son.

Some of these feasts focus on Christ directly; others on the Theotokos and how her life is woven into His.

Together they trace a pattern:

from preparation and promise,

through Incarnation and Pascha,

to the gift of the Spirit

and the glorification of humanity.

You don’t have to memorize the dates or expect a quiz. Just knowing that these are the “big twelve” helps you notice when they come around in parish life and show up in the weekly worship guide.

The Four Great Fasts & the Little Rhythms

If the feasts are like going up to the mountaintop, the fasts are the rigorous training paths that prepare us to ascend. While many of the specifics belong in conversation with a priest, we can certainly sketch a lay of the land.

The Four Major Fasts

Great Lent - The long, sober season before Holy Week and Pascha. We’ve already built a full guide for this one.

Nativity Fast (Advent) - The 40 days leading up to Christmas (starting November 15 on the New Calendar), a time of repentance and quiet expectation as we move toward the Nativity of Christ.

Apostles’ Fast - A variable‑length fast between All Saints Sunday (the Sunday after Pentecost) and the feast of Saints Peter and Paul (June 29). It honors the Apostles and our own calling to be witnesses for Christ in this life.

Dormition Fast - A two‑week fast (August 1–14) preparing for the Dormition of the Theotokos—shorter and more concentrated, with a strong theme of turning to Mary’s intercession.

Weekly and Smaller Rhythms

Wednesdays and Fridays - Traditionally these are fast days all year (with a few exceptions), remembering Christ’s betrayal (Wednesday) and Crucifixion (Friday). Fasting here is often simpler than in the big seasons, but it keeps the Cross near.

Fast‑free periods - The Church actually builds in seasons of no fasting before and/or after a fast: Bright Week after Pascha, the week after Christmas, after Pentecost, and a few others. These are intentional exhale moments: the Church doesn’t just tighten; she also relaxes and feasts.

The big idea: fasting is not a liturgical punishment. It’s a way the Church trains us, over and over, in repentance, watchfulness, mercy, and deeper joy. How exactly you keep these fasts depends on your situation and must be worked out with your priest, not an online list downloaded at midnight.

Father Steven Kostoff explains it this way:

The festal cycle of the Church sanctifies time. By this we mean that the tedious flow of time is imbued with sacred content as we celebrate the events of the past now made present through liturgical worship. Notice how often we hear the word “today” in the hymns…: “Today let us, the faithful dance for joy….” “Today the living Temple of the holy glory of Christ our God, she who alone among women is pure and blessed….” “Today the Theotokos, the Temple that is to hold God, is led into the temple of the Lord….”

Again, we do not merely commemorate the past, but we make the past present. We actualize the event being celebrated so that we are also participating in it. We, “today,” rejoice as we greet the Mother of God as she enters the temple “in anticipation proclaiming Christ to all.” Can all—or any—of this possibly change the “tone” of how we live this day? Is it at all possible that an awareness of this joyous feast can bring some illumination or sense of divine grace into the seemingly unchanging flow of daily life? Are we able to envision our lives as belonging to a greater whole: the life of the Church that is moving toward the final revelation of God’s Kingdom in all of its fullness?

Everyday Texture of the Year, Saints, & Seasons

If you look again at that second calendar on the fridge, you’ll notice that every day has saints. Not just the super famous ones everyone has heard of: local saints, martyrs, ascetics, bishops, holy fools. I’ve heard some joke that icons are like Pokemon, you gotta collect them all—I think it’s more like a family photo album that never seems to run out of pages or forget about family members.

A few features worth noticing:

Namedays - In many Orthodox homes, your main celebration may not be your birthday but your saint’s day—your nameday. It’s a way of rooting your identity in a holy person who has already walked the path you’re on. In my family, we try to honor these days with well wishes and special prayers at the very least.

Seasonal Feelergies - How the seasons “feel” to the pilgrim journeying through them.

Great Lent: sober, penitential, introspective.

Pascha and the weeks after: bright, triumphant, almost giddy with “Christ is risen.”

Dormition: quietly contemplative, looking to the Mother of God as the first fully redeemed human.

Local and parish feasts - Your parish probably has a patronal feast (St. George, St. Nicholas, etc.), which is like the parish’s birthday. These days shape the local church’s sense of itself in a unique way.

Anniversaries and other sacraments - The Church also sanctifies time by commemorating the faithful departed at appropriate intervals; blessing us shortly after birth, naming us, welcoming us into the Church, and baptizing us into Christ; blessing the foundation of marriage in hopes that with time it would blossom into a new family; and so on.

The Saturday of Souls - We believe God’s love extends beyond the grave and that remembrance itself is an act of mercy, so the Church sets apart certain Saturdays throughout the year to commemorate and pray for the departed. Part of this is the recognition that death does not sever our bond with loved ones or break the communion of saints; through the Divine Liturgy and our prayers, we offer what comfort and intercession we can for those who have fallen asleep.

Memorial Services and the 40-Day Cycle - The Church establishes rhythms of remembrance: the 40-day memorial, the one-year memorial, and anniversary commemorations invite us to gather repeatedly around the departed, offering prayers and the Divine Liturgy on their behalf; these intervals honor both the journey of the soul after death and our own need to grieve, celebrate their life, and maintain the living bond between the Church on earth and those who have departed. Love and intercession do not end for us when the funeral does.

And then there’s the calendar question that looms in the background: Old Calendar vs New Calendar. Some Orthodox follow the older Julian calendar for fixed feasts, which currently runs 13 days “behind” the civil (Gregorian) calendar; others follow the Revised Julian (“New Calendar”) for fixed feasts while keeping Pascha together. (If this is your first time hearing of this, you might want to read that paragraph again, because I actually was talking about three calendars there and I can almost guarantee you’re lost!)

You don’t need to become a calendar apologist. It’s enough to know:

Faithful Orthodox Christians exist on both systems.

I’ve been on each calendar, and I had to wash my undies the same amount of times, no matter the calendar.

Pascha is kept together across canonical Orthodoxy.

Despite the hype online, Pascha hasn’t changed for us.

The divisions and arguments around the calendar are tragic.

But the calendar problem is not a clever puzzle to solve in your first year, but represents rather what is on-the-ground a sometimes challenging situation for unity in the faith.

The task is simple if you wish to be a faithful Orthodox Christian: follow the calendar of your bishop and your parish, pray for the healing of divisions, and let the feasts and fasts you’re actually living shape your heart. And since we follow ultimately the same feasts and fasts, and share a common Pascha, the division is actually much less than it appears from the outside.

As Saint Paul puts it in Romans 14:5-6, when addressing matters of fasting, feasting, and observing holidays, we should also honor one another when we honor the Lord with our sanctification of time:

5 One person esteems one day as better than another, while another esteems all days alike. Each one should be fully convinced in his own mind. 6 The one who observes the day, observes it in honor of the Lord. The one who eats, eats in honor of the Lord, since he gives thanks to God, while the one who abstains, abstains in honor of the Lord and gives thanks to God.

The task is simple if you wish to be a faithful Orthodox Christian: follow the calendar of your bishop and your parish, pray for the healing of divisions, and let the feasts and fasts you’re actually living shape your heart.

How a Normal Person Can Live the Church Year

All of this may still sound like a lot. So what does it look like for an ordinary catechumen or new Orthodox Christian to begin to live this out?

A few suggested starting points:

Let Sunday really be Sunday. If you only do one thing, let Sunday Divine Liturgy become non‑negotiable in your week. Build outward from there.

Choose a handful of feasts to “own.”

Many parishes will hold weekday liturgies for one or more saints or feasts above—depending on the parish and the feast, these services may be offered in the morning or the evening. Carving out some time to go can be extremely rewarding. Maybe consider:

Your patron saint’s day (nameday).

The feast of your parish’s patron.

One or two feasts that particularly move you (Theophany, Dormition, Pentecost), or other services provided throughout the year.

Make a point of being at the services in person if you can, and mark them at home with a special meal, light candles during prayer, or perhaps have a short family prayer to mark the particular feast day. Perhaps you might pray one of the hymns to one of the saints of the day during your morning or evening prayers—or maybe find an excuse to talk about the life of the saint with one of your friends or family members who would enjoy such conversation.

Take the fasts seriously—but sanely. Talk to your priest about how to begin observing:

Wednesdays and Fridays,

And several of the “main” services your parish offers during the year.

Aim for faithfulness, not heroics.

Bring it home in small ways. You don’t need to turn your home into an elaborate domestic monastery. But you can:

Light a candle or lampada on feasts, maybe even some incense from a monastery or parish bookstore.

Read a short life of the saint of the day now and then—for the more ambitious, maybe one a day.

Let your conversations, media, and meals reflect the season. The general thought pattern is that it is quieter in Lent, more celebratory at Pascha—many will even cut out social media and entertainment like movies during the fasting seasons.

Over time, you’ll find that you’re not just looking at two calendars on the fridge—you’re learning to inhabit one through the other. Work and school and civic life won’t disappear, but they’ll be nested inside a bigger story: creation, fall, Incarnation, Cross, Resurrection, Spirit, kingdom.

And as you move through that story again and again, the point is not to collect feast days like stamps, Pokemon cards, or refrigerator magnets. The point is to let Christ’s life, and the lives of His saints, quietly reshape your own sense of what a year—even an ordinary, busy, messy year— is for.

In conclusion, let’s hear Professor Theodore Stylianopoulos:

What is the significance of the liturgical year?

The liturgical year is a way of discipline in prayer, a pattern of worship, an anchor of support for the life of the Church. But it also has deeper significance. The late George Florovsky, an eminent Orthodox theologian of blessed memory, has taught us that worship is a response to the call of God who has already made known His redeeming love to us through decisive events culminating in the person and ministry of Jesus Christ. Worship has two major aspects: remembrance (anamnesis which means not only historical remembrance but also re-living the events commemorated) and thanksgiving (including praise and doxology).

Thus the liturgical year, by bringing unceasingly before us God’s mighty deeds of salvation and the reality of God’s kingdom in our midst, is the sanctification of time and thereby the true fulfillment of both personal and corporate aspects of our lives as Christians. Far from being simply a calendar, the liturgical year in the life of the Church—the life of Christians living in community as brothers and sisters—in awareness of God’s kingdom, remembering the entire communion of Prophets, Apostles, Saints and all of God’s people on earth and in heaven, being renewed by God’s saving love, helping one another, witnessing to Christ’s good news, and waiting for the fullness of the coming kingdom according to God’s timing.

“If we live, we live to the Lord, and if we die, we die to the Lord” (Rom. 14:8).

Orthodox worship proclaims the centrality of Christ. The liturgical year celebrates the presence of the mystery of Christ in the life of the Church and seeks to make the living Christ a renewing lifesource for every Orthodox Christian.

Glory to God for all things!

P.S. We had a sudden influx of readers this last week, so welcome to everyone just joining us! We provide 1-2 posts a week of primarily catechetical material, often with an emphasis on the “Deuterocanonical” books of the Orthodox Old Testament. Our content is frequently aligned with something we are doing in our in-person teaching ministry at Saint Mark Greek Orthodox Church in Boca Raton, Florida. We have a ton of great content planned for this year, and lots in the archives—we welcome your requests for future content via email or in the comment boxes on the site itself.

This is so helpful, thank you 🙏