The King of Heaven and His People on Earth

Episode 12 of “Bad” Books of the Bible is live! Tell a friend (or an enemy) about it.

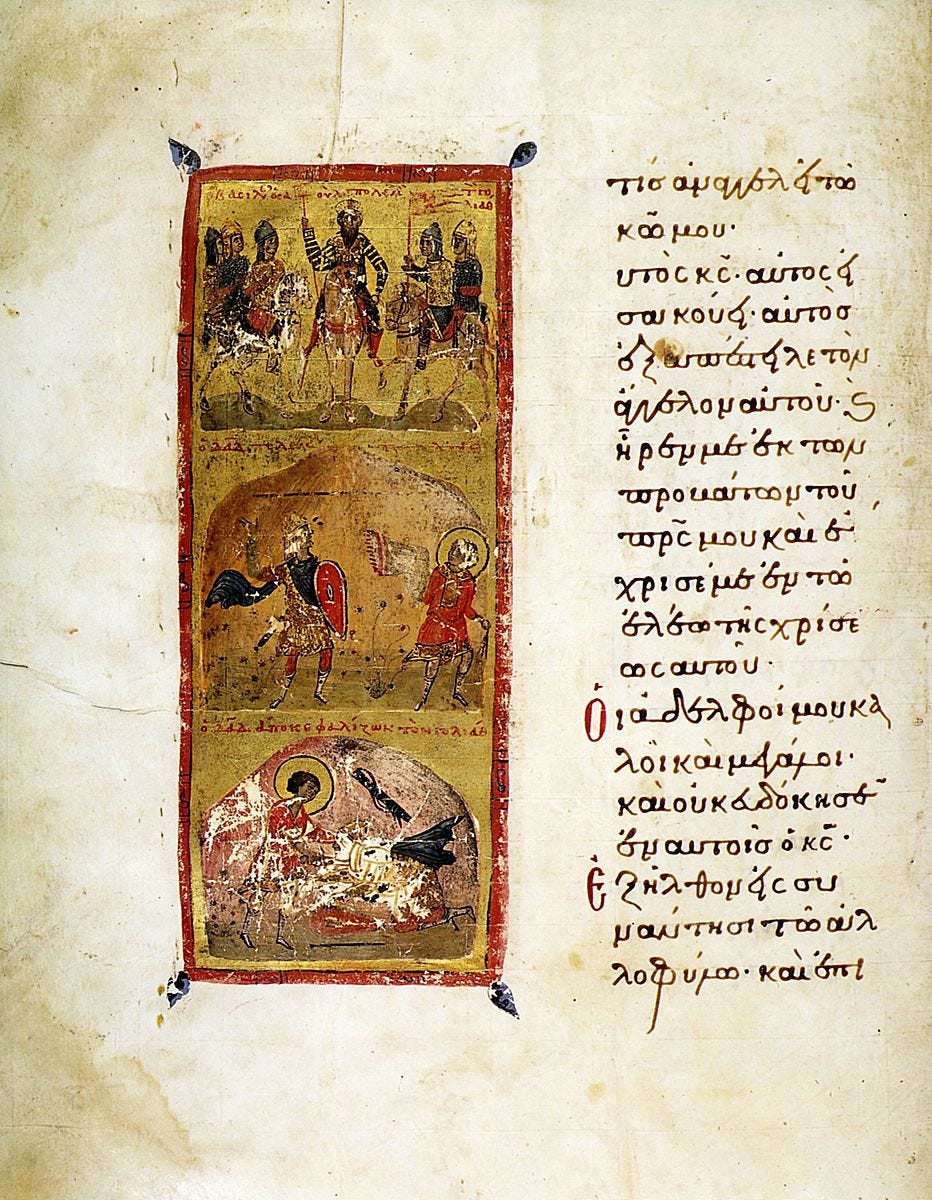

It’s Greek to me

The Book of Tobit is all about being a faithful Israelite. But there’s more going on here. After all, we—a couple of Gentiles—are reading it. And that’s saying something if you think about it.

Susan Garrett, professor of New Testament at Louisville Presbyterian Theological Seminary says this about the Book of Tobit:

Although Tobit, Tobias, and Sarah play no role in major events in Israel’s history, they perfectly embody the ideals of the people as a whole. Their eyes are focused squarely on God and they are wholly devoted to serving God.1

And, of course, that could be go for any believer, really—Jew or Gentile. But how would a faith first practiced among Jews in the language of Hebrew find its way outside those confines?

Let’s go back to our old friend St. Bede. We talked about how he reads this book with an allegorical lens. He looks to the money that Tobit entrusted with Gabael—the ten silver talents—and compares them to the scriptures translated from Hebrew to Greek, the version of the Old Testament called the Septuagint after the legend of its seventy translators, abbreviated as LXX.

He says,

The people of God entrusted to the Gentiles through the seventy translators the knowledge of the divine law that is contained in the Decalogue in order thereby to free them from the indigence [poverty] of unbelief. . . . The Gentiles received the Word of God from the people of Israel through the medium of translation because now after the Lord’s incarnation they also understand it spiritually and work at acquiring the riches of the virtues.2

We’ve talked before about the textual history of Tobit. It was first written most likely in Aramaic or possibly Hebrew, then translated into Greek. The Greek version of the book is what we’ve examined through this series so far. And that’s hugely significant. Not only in terms of the historical transmission of the book, but also our ability to read it and recognize it as scripture and to be illumined by it ourselves.

The Bible as world literature

Consider this from the historian of Christianity, Jaroslav Pelikan:

Whatever the precise details of its composition or its standing within the Jewish community of faith, the creation of the Septuagint brought it about that the Bible became, willy-nilly, part of world literature. Anyone who could read the Odyssey could now read the Book of Exodus. . . . It had long been part of the hope of Israel, voiced by the prophets, that peoples ‘far and remote’ would finally come to Mount Zion and learn the Torah, which was intended to be revealed by the One True God for all peoples, not only for the people of Israel.3

The book of Tobit is a chapter in that unfolding story. Remember that Tobit was like the Torah incarnate. Remember also that his life foreshadows the Sermon on the Mount. And we access that holy life, that righteous example, not through Hebrew or Aramaic—but through Greek.

This is what laid the foundation for the conversion of the Gentiles. And that’s something not only foretold by the prophets, as Pelikan says, but also the Book of Tobit itself. We find our way to Tobit’s statements about that as we move through his concluding praise and final testament.

Tobit’s final praise (Tobit 13.1–8)

In our last episode, Raphael ascends, and the narrator says, “They kept blessing God and singing his praises.” In fact, they kept doing it for a whole additional chapter. Chapter 13 contains Tobit riffing on several of the themes we’ve seen so far. In the next two chapters they’re brought together in a coda.

The chapter begins with Tobit launching into a psalm (rendered here as prose because of formatting limitations):

Blessed be God who lives forever, because his kingdom lasts throughout all ages. For he afflicts, and he shows mercy; he leads down to Hades in the lowest regions of the earth, and he brings up from the great abyss, and there is nothing that can escape his hand.

Scholars note that the original author is likely not speaking of the resurrection as such, but that reading is pretty much impossible for Christians to miss on this side of Pascha and the resurrection of Christ.

Tobit tells his listeners, “Acknowledge [God] before the nations, O children of Israel.” These “nations” are the Gentiles we’ve been talking about. God has disciplined his people by driving them into exile. But their witness in exile will draw the Gentiles into the people of God.

Tobit’s story is emblematic of Israel’s suffering. “He will afflict you for your iniquities, but he will again show mercy on all of you.” If the people repent, “He will gather you from all the nations.”

By acknowledging God in exile, exiles like Tobit are a witness. They “show his power and majesty to a nation of sinners: ‘Turn back, you sinners, and do what is right before him; perhaps he may look with favour upon you and show you mercy.’” This gives him the hope to say that “all people [will] speak of his majesty, and acknowledge him in Jerusalem.”

Affliction, mercy, and a bright light (Tobit 13.9–12)

Tobit circles back on the affliction-mercy motif. He’s used it about himself, then Israel, now he applies it to Jerusalem. By acknowledging God amid their affliction, he will have mercy and cause the city to be rebuilt.

Chronologically speaking, this is a bit odd because the city and temple are still standing during the historical moment the book presents; the temple is destroyed in 586 BC by Nebuchadnezzar. But for the author and earliest readers of the book this was not only history, the temple had been rebuilt.

Tobit speaks of this rebuilt city will be a beacon.

A bright light will shine to all the ends of the earth; many nations will come to you from far away, the inhabitants of the remotest parts of the earth to your holy name, bearing gifts in their hands for the King of heaven.

And here’s another one of those lines it’s hard for Christians to read without reference to Christ: “gifts in their hands for the King of heaven.” Anyone see the three wise men here? The Gentiles are on their way in.

The restoration of Jerusalem (Tobit 13.13–17)

In the setting of Tobit the restoration of Jerusalem is prophecy, but the book itself is was written long after the rebuilding of Jerusalem and the temple. Still, there’s an eschatological edge to the restoration of Jerusalem here:

For Jerusalem will be built as his house for all ages. . . . The gates of Jerusalem will be built with sapphire and emerald, and all your walls with precious stones. The towers of Jerusalem will be built with gold, and their battlements with pure gold. The streets of Jerusalem will be paved with ruby and with stones of Ophir.

Virtually the same imagery is picked up in Revelation 21:

The angel who talked to me had a measuring rod of gold to measure the city and its gates and walls. . . . The wall is built of jasper, while the city is pure gold, clear as glass. The foundations of the wall of the city are adorned with every jewel; the first was jasper, the second sapphire, the third agate, the fourth emerald, the fifth onyx, the sixth carnelian, the seventh chrysolite, the eighth beryl, the ninth topaz, the tenth chrysoprase, the eleventh jacinth, the twelfth amethyst. And the twelve gates are twelve pearls, each of the gates is a single pearl, and the street of the city is pure gold, transparent as glass.

Last will and testament, again (Tobit 14.1–5)

“So ended Tobit’s words of praise,” the narrator tells us. And then we get the Tobit’s last will and testament—again.

Different versions present Tobit’s age differently, but he made it past a hundred. In another Joban turn, he not only regained his sight, but he regained his prosperity—from which he still gave alms.

But not all is well in Nineveh. Tobit is on his deathbed, and he calls Tobias. He tells him to hurry off to Media.

I believe the word of God that Nahum spoke about Nineveh, that all these things will take place and overtake Assyria and Nineveh. . . . It will be safer in Media than in Assyria and Babylon. . . . Whatever God has said will be fulfilled and will come true; not a single word of the prophecies will fail.”

Weirdly, the long version of the book (GII) says Nahum; the short version (GI) says Jonah. Whichever prophet we’re talking about, Tobit believes the validity of their words.

And then the affliction-mercy motif shows up again. He says the Israelites will be taken captive, that Samaria and Jerusalem will be desolate. And the temple will be destroyed. That’s the affliction. “But God will again have mercy on them, and God will bring them back into the land.” That’s the mercy. And this is when Jerusalem will be rebuilt, he says, “in splendour.”

Tobit also returns to the theme of the Gentiles.

Conversion of the Gentiles (Tobit 14.6–7)

“Then the nations in the whole world will all be converted and worship God in truth. They will all abandon their idols, which deceitfully have led them into their error; and in righteousness they will praise the eternal God.”

This idea of the Gentiles converting and streaming into Jerusalem is clearly an important theme, covered not only in chapter 13 but again here. It’s a theme that can be found shot through the Old Testament.

Isaiah 2.3: “Many peoples shall come and say, ‘Come, let us go up to the mountain of the Lord, to the house of the God of Jacob; that he may teach us his ways and that we may walk in his paths.’” This is a reference to the Gentiles coming in.

Isaiah 60.3: “Nations shall come to your light, and kings to the brightness of your dawn.”

Zechariah 8.20, 22: “Peoples shall yet come . . . Many peoples and strong nations shall come to seek the Lord of hosts in Jerusalem. . . .”

And here’s a passage from a book that counts as truly apocryphal in Jerome’s sense—unless you’re Ethiopian because it’s actually in your Old Testament canon. We mentioned in the last episode the list of archangels and how some of those names are mentioned in 1 Enoch.

One of those archangel passages closes with the command to cleanse the earth:

Make the earth clean from all uncleanness and from all wrongdoing and from all sins . . . Wipe it away. And all the people will be serving and blessing and worshiping me. And the whole earth will be made clean. . . . (1 Enoch 10.20–21, Lexham English Septuagint)

Another version of that verse says: “All the children of men shall become righteous, and all nations shall offer adoration and shall praise Me, and all shall worship Me.”

These statements are made in eschatological hope. In Matthew 8.11–12 and Luke 13.28–29 Jesus speaks of this future hope. Here it is from Matthew: “Many will come from east and west [Luke adds north and south] and will recline at the table with Abraham and Isaac and Jacob in the kingdom of heaven.” In Matthew this statement comes after the healing of the Roman Centurion’s daughter.

So many more passages we could add to this. But it’s worth stopping in Romans 15. St. Paul speaks of himself as the apostle to the Gentiles, and in this passage he strings together a bunch of verses from Deuteronomy, Psalms, 2 Samuel, and Isaiah about Gentiles praising God and the root of Jesse—Jesus—being the one in whom the Gentiles will have hope.

Not surprisingly, you’ll find notes in various Bibles that Paul is following the Septuagint wording of some of these passages. The New Testament in general quotes from the Old Testament in Greek.

Tobit sees a future of Jews and Gentiles together worshiping the one God, and this takes us full circle: Here’s Bede’s statement about the scriptures held in trust now paying dividends coming alive.

Do right and split (Tobit 14.8–11)

Still offering his last will and testament, Tobit shifts back to serving God and doing acts of mercy, that is, almsgiving. He encourages Tobias to command his children: “be mindful of God and to bless his name at all times with sincerity and with all their strength.”

And then he says split town: As soon as your mother Anna dies, bury her by me, and hit the road. Why? Because Nineveh is about to fall. Tobit mentions the fate of his nephew Ahikar—remember him? Ahikar’s own nephew, Nadab, who he raised tried to kill him. But Ahikar was saved. How? The book provides no details, but Tobit says because Ahikar did works of mercy. “So now, my children, see what almsgiving accomplishes, and what injustice does—it brings death!”

And then Tobit himself dies: “But now my breath fails me.”

Back to Ecbatana (Tobit 14.11–15)

The narrator says those with Tobit laid him on his bed and he died, after which he was given “an honorable funeral.”

At some point later Anna dies. Tobias buries her next to his father, Tobit, and then he takes his whole crew back to Ecbatana to live with his in-laws. Ultimately, he inherits the rest of Raguel’s property.

And then he also goes the way of all flesh. Verse 14 says that he made it to 117 years (long version, 127 years in the shorter version). By then Nineveh had fallen as predicted and Tobias praised God for bringing ruin on the place. It concludes by saying, “he blessed the Lord God for ever and ever. Amen.”

Coming next week . . .

We take listener questions and riff on some of the themes we appreciated in the book. If you have any questions of your own, drop them in the comments below.

And don’t forget to share the show with anyone you know who’s a fan of the so-called Apocrypha or just apocry-curious.