Why Christianity Helps Makes Sense of Life, Death, and Everything in Between

Five reasons why the Christian faith both answers our biggest questions and meets our deepest needs

Why I’m a Theist and a Christian

“Why does God seem so elusive?” It’s a fair question. If God is real, why doesn’t He make Himself just a bit more obvious? Why do doubts creep in on quiet nights? I’ve wrestled with these questions myself—as many of us do. Francis Thompson once described God as “The Hound of Heaven,” relentlessly pursuing us, even when we aren’t fully aware of Him. But He doesn’t hunt us down with blaring sirens. He whispers.

In The Elusive God, Paul Moser suggests that God’s seeming hiddenness isn’t proof of absence, but an invitation. If God were undeniably obvious and inescapable, would we truly respond in love, or merely in resignation? Faith, on the other hand, demands more of us. It’s not automatic, but it isn’t irrational either—it exists in the space between evidence and relationship, between logic and trust.

For years, I’ve sought answers both in faith and in honest inquiry, and I’ve found the following five reasons why I remain a theist and a Christian to be among the most compelling to me personally. These reasons don’t just speak to rationality; they also connect with meaning, hope, and the penetrating questions we all face.

1. The Universe Demands a Necessary Cause

In moments of doubt, I often think about the sheer existence of the universe. Where did it come from? Why is there something rather than nothing? The principle of cause and effect suggests that everything contingent (everything that could hypothetically not exist) must have a cause. But that chain of causality can’t go on infinitely—it terminates, logically, in something necessary, uncaused, and eternal.

Frank Turek, in Stealing from God, argues that even skeptics lean on truths that only make sense with God. They rely on logic, morality, and the reliability of natural laws—things that don’t arise by chance but require a transcendent foundation. Our universe had a beginning, confirmed both by science (Big Bang cosmology) and reason, which means it depends on a cause outside of itself. That cause, as philosophers argue, resembles the God who Christians worship—not an impersonal force but an intelligent, purposeful Creator.

In The Privileged Planet, Guillermo Gonzalez and Jay Richards argue that Earth isn’t just randomly habitable—it’s uniquely positioned for life and, remarkably, for scientific discovery. They point out that factors like our planet’s location in the galaxy, its distance from the Sun, and the rare alignment that allows phenomena like solar eclipses (crucial for studying the cosmos) suggest a deliberate setup. It’s as if the universe isn’t just there but is arranged so we can both live in it and understand it. This correlation between habitability and discoverability nudges me toward the idea of design—a Creator who not only initiated the universe but crafted it with purpose, inviting us to explore and know more about His creation.

2. We’re Wired for God

Have you ever stopped to wonder why belief in God or the supernatural is so deeply ingrained in humanity? Across every culture, every era, people have worshipped something beyond themselves. From primitive animistic spirits to monotheistic faiths, this “natural religiosity” is inescapable.

Why does this matter? Evolutionary psychologists argue that belief in God has survival value—it strengthens group cohesion and morality. While there’s truth in that, it doesn’t explain why this particular belief is so universal. Alvin Plantinga, a prominent Christian philosopher, suggests that our universal religious impulse is more than survival instinct; it is a sign of a deeper truth. He calls it the sensus divinitatis, or the “sense of the divine,” an intrinsic awareness of God’s presence placed within us.

This resonates with me. If atheism were true, if the universe was nothing more than a blind and indifferent accident, wouldn’t widespread religious belief be a strange mistake of evolution? But if Christianity is true, this “God-sense” isn’t an accident—it’s a clue.

Deep down, we’re wired for connection with God, because as the Bible poetically puts it, He “set eternity in the human heart” (Ecclesiastes 3:11).

3. Faith Fosters a Flourishing Society

Let’s shift gears. Even if people believe in God, is religion actually helpful? Or is it just a source of tribalism and division? In my own experience, and from what I see in history, Christianity has done far more good than harm.

Communities shaped by Christian ethics have left a deep impact on the world. Hospitals, universities, and charities often trace their origins to Christian convictions about the value of human life. C.S. Lewis, in Mere Christianity, argues that belief in a moral lawgiver grounds society’s sense of right and wrong. Without God, moral frameworks often reduce to preferences—we lose any absolute basis for good and evil.

Philosophers like Alasdair MacIntyre weigh in here too. In After Virtue, he cautions that moral systems not rooted in a common tradition lose their integrity; they become fragmented and arbitrary. Christianity offers a worldview that sees every life as endowed with dignity because humanity reflects God’s image. That’s a powerful foundation for justice, mercy, and human flourishing.

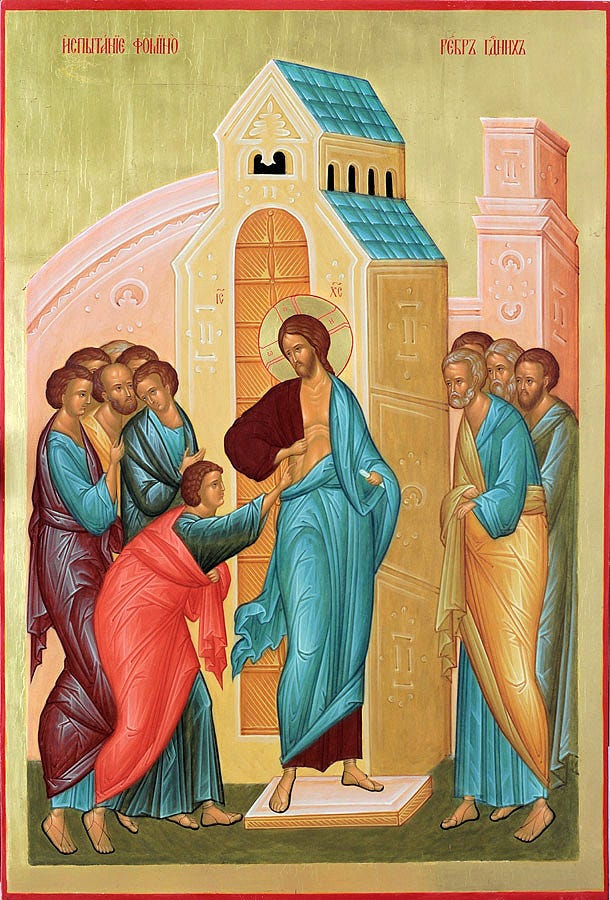

4. The Resurrection Explains Christianity’s Rapid Growth

Let’s get specific. Christianity didn’t start as a cultural institution—it began with a small band of followers who believed, against all odds, that a “godman” named Jesus had risen from the dead. Within decades, this audacious proclamation spread across the Roman Empire. How?

In his book Resurrection, Hank Hanegraaff notes that nothing short of a literal, historical resurrection explains the explosive growth of Christianity. These early believers weren’t preaching vague spirituality. They claimed to be eyewitnesses of Jesus’ resurrection, basing their faith on an empty tomb and post-crucifixion appearances.

What’s more, they were willing to suffer and die for this belief. Consider this: would you willingly endure torture, exile, and death for something you knew was false? They didn’t just believe Christianity—they’d seen it embodied in the resurrected Christ. Skeptics may dismiss the supernatural, but no secular theory can account for why so many people, including skeptics like Saul of Tarsus, surrendered their lives to an executed carpenter from Nazareth.

5. Christianity Confronts Death’s Power

I’ll be honest: one reason I hold fast to Christianity is personal. Death haunts every one of us. Each loss feels like a permanent wound, a reminder of how fragile life is. And yet Christianity looks death squarely in the face and declares, “This is not the end.”

It’s not a stretch to say Orthodox Christianity is an “anti-death cult.”

Saint Paul’s words in 1 Corinthians 15 ring out in triumph: “O death, where is your victory? O death, where is your sting?” Early Christians believed that in the resurrection of Jesus, God had defeated death itself. Fr. Alexander Schmemann, in For the Life of the World, captures this beautifully: Christ didn’t simply “cheat” death or evade it—He entered it, broke its power, and transformed it from within.

This defiance of death isn’t just abstract theology. Personally, it’s been a lifeline. Christianity doesn’t pretend death doesn’t hurt—it grieves with us—but it also assures us that God is ultimately redeeming even this greatest of enemies. For me, that’s a hope worth holding onto.

Faith Between Trust and Reason

None of these reasons “prove” Christianity in a scientific sense, of course. But they form a mosaic of a more coherent, compelling picture of reality. The universe’s beginning points to God. Our deep-seated “God-sense” confirms it. Faith transforms societies and individuals for the better, the resurrection explains Christianity’s unlikely rise, and the Gospel offers hope in the face of life’s greatest test.

If you’ve wrestled with doubt, I hope these reflections encourage you. Faith isn’t blind; it’s an act of trust based on evidence and experience. Maybe God seems elusive because He invites us not to resignation, but to love—and love, after all, can never be forced.

Bibliography

Gonzalez, Guillermo, and Jay W. Richards. The Privileged Planet: How Our Place in the Cosmos Is Designed for Discovery. Washington, D.C.: Regnery Publishing, 2004.

Hanegraaff, Hank. Resurrection. Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 2000.

Lewis, C.S. Mere Christianity: A Critical Edition, ed. Alister E. McGrath. London: William Collins, 2024.

MacIntyre, Alasdair. After Virtue: A Study in Moral Theory. 3rd ed. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 2007.

Moser, Paul K. The Elusive God: Reorienting Religious Epistemology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

Plantinga, Alvin. Warranted Christian Belief. New York: Oxford University Press, 2000.

Schmemann, Alexander. For the Life of the World: Sacraments and Orthodoxy. Crestwood: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1973.

Thompson, Francis. “The Hound of Heaven.” In Poems. London: Burns & Oates, 1893.

Turek, Frank. Stealing from God: Why Atheists Need God to Make Their Case. Colorado Springs: NavPress, 2014.

The richest and most powerful men on the planet are trying to set themselves and their AI tyranny as 'homo deus. True faith is more important than ever.